Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

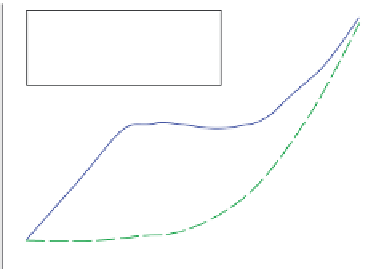

Muscle length-tension relationship

Passive force

Active force

Total force

Muscle length

FIGURE 6.4

Schematic of the muscle length-tension relationship, demonstrating the active, passive

and net tension produced as a function of muscle length.

force-length relationship (

Gordon et al., 1966

). In addition to this active force,

muscle and tendon exhibit passive elastic properties, such that stretching a muscle

eventually produces passive force, like a spring. If you combine these active and

passive forces, the net force from a muscle typically increases with muscle length,

but with a curvilinear plateau in the region of optimal muscle length (

Figure 6.4

).

The torque produced about a joint is the product of the muscle force and its

moment arm with respect to the joint center of rotation. Thus, torque is a function

of both muscle force-producing capability and the mechanical advantage afforded

by the muscle-tendon complex. As joint angles change throughout the range of

motion, this mechanical advantage changes. These changes can be specific to

each joint, thus no one relationship can be modeled for all joints (

Frey-Law et al.,

2012b

). Thus, the torque-angle relationship does not always appear to be consis-

tent with the force-length relationship.

Population-specific factors that influence strength include: male versus female;

young-versus old-adult; and active/trained versus sedentary cohorts, to name a

few. Typically men exhibit approximately 50% greater peak torque than females

but this too can vary across joint regions (

Frey-Law et al., 2012b

). As mentioned

above, these sex differences result primarily from cross-sectional area as opposed

to the inherent muscle properties for men and women (e.g., specific tension of

muscle). Certainly this does not discount systemic physiological differences

between men and women, including sex differences in the hormonal milieu, from

playing a strong role in muscle strength. It does, however, suggest the contractile

proteins are not in and of themselves the source of these differences per se, but

rather the number of these muscle fibers in parallel. Accordingly, digital humans

(DHs) need to be specific to male versus female avatars not only in physical

anthropometry (e.g., height and weight) but also in strength properties.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search