Graphics Reference

In-Depth Information

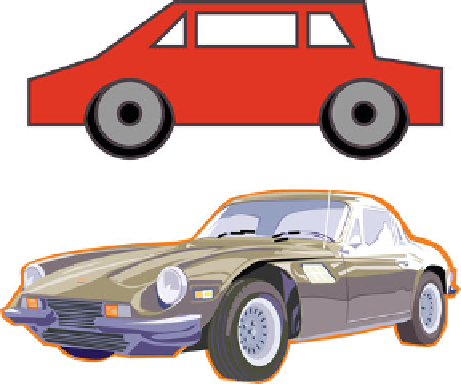

Fig. 3.1

A schematic and

non-schematic version of a car

3.2.1

Schematic

A 3D subject such as an automobile has a specifi c appearance but it also has structure

that is dictated by the functions of all its parts. Wheels must roll, therefore they are

round. This does not mean that all tires are alike, but that they all share the character-

istic of being round. A

schematic

level of observation would lead to a round tire, but

not a tire that is distinguishable from others made for different purposes, by different

manufacturers, or in different time periods. At a larger level, a schematic representa-

tion of a vehicle pays attention to its topology, how the parts are connected and how

many parts there are, but not their specifi c appearance. A vehicle made this way

might resemble a sedan, but would not be any specifi c sedan (Fig.

3.1

).

Schematic representations ignore the measurements and specifi c properties of

their target object. When an artist incorporates schematic representation into their

style, it is because they are not suffi ciently concerned with exploring and analyzing

the differences between similar objects. The question they should ask when observ-

ing a subject is not “What is here?” but “Why is this different from every other

example?” An artist with schematic level observation skills will be able to make 3D

objects, but will not be able to make convincing realistic 3d objects without fi rst

improving their observation skills.

3.2.2

Symbol

Symbol

observation

is related to

simplifi ed, exaggerated,

or

stylized

representations.

Characters, props, and environments in television cartoons tend to be stylized repre-

sentations of their subjects. Mickey Mouse doesn't look like a real mouse, but he has

Search WWH ::

Custom Search