Graphics Programs Reference

In-Depth Information

Sculpting Concepts

With Blender set up nicely for sculpting, let's get to

it. In general, we'll sculpt from coarse to fine, just

like sculpture in the real world. By beginning with

the broad structure of the final product we want

to achieve and working toward the fine details, we

reduce the number of steps we need to undo in

order to correct errors.

This section will introduce you to some general

concepts in the order I think about them when

sculpting.

Volumes and proportion

When beginning to

sculpt, first set out the rough shape of your sub-

ject; in other words, create a rough volume for

each component of your overall figure. When

sculpting a character, you should block out the

volumes of the legs, arms, torso, head, hands,

and feet. This is accomplished partly by creat-

ing a good base mesh. For example, we already

created the basic shape of the Bat Creature

character in Chapter 4; however, this can still

be refined and improved while sculpting to give

a better feel for the size and overall shape of the

model.

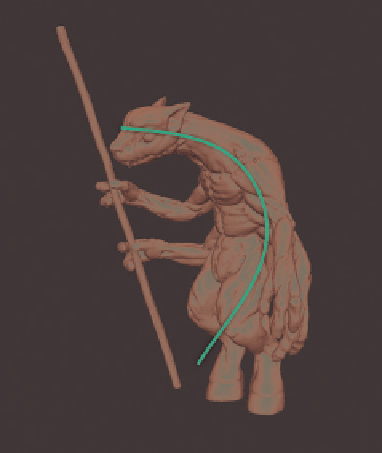

Figure 6-16: Try to establish smooth curves that

flow through your characters

these planes include those along the side of the

head, along the jawline and chin, and down the

bridge of the nose. Smaller secondary planes

form the shapes of the ears, lips, and nostrils.

(You don't actually need to define the planes

of your model too rigorously, as they will be

smoothed out later, but it is important to know

and roughly mark in where they are.)

Gesture

Gesture describes the stance of a char-

acter and the flow of forms from one body part

to another. This stage applies more to posed

characters but is an important part of creating

a good neutral pose, and even applies when

sculpting inorganic forms. Key at this stage is

that the forms of the body are connected by

smooth, flowing curves. You should usually be

able to draw a smooth curve through your char-

acter's pose, as shown in Figure 6-16.

Coarse details and anatomy

Once you've finished

creating the main volumes and planes of your

sculpture, you'll find that many of the anatomi-

cal details are actually already present, though

there are still many anatomical features to be

added to the final sculpt. Achieving anatomi-

cal realism in your sculpts takes practice and is

a matter of gathering and studying anatomical

references and then placing and refining those

anatomical landmarks on your sculpt.

One way to begin filling in the details is to

start with the major muscle groups and skeletal

landmarks and then progress to smaller details

like the musculature and small features like

fingers, ears, eyes, and so on. See “Planes” on

page 79 to learn how I accomplished this for

the Bat Creature.

Planes

By planes, I mean breaking down and

simplifying the form of the object into flat

planes—areas of the object that form broadly

flat surfaces rather than polygons. The direction

and placement of the planes in your sculpture

determine how the surfaces of your objects

catch light, creating patterns that in turn play a

large part in how we read and recognize shapes.

Even though you'll ultimately smooth out

these planes, they'll still influence your finished

object. For example, the planes in a human

or humanoid character are largely defined by

the object's major anatomical landmarks, such

as the bony parts of the skull, ribcage, collar

bones, and pelvis. In Figure 6-17, the main large

planes are defined by the shape of the skull;

Fine details and surface texture

Finally, we prog-

ress to fine details, like wrinkles and pores

in skin, or technical details in a hard-surface

model (see Figure 6-18). This is a fun stage

Search WWH ::

Custom Search