Graphics Programs Reference

In-Depth Information

sizes. For example, soft shadows don't need

high-resolution shadow buffers, and crisp,

hard-edged shadows don't need lots of samples.

Once you have lighting you like, try to deter-

mine which settings you can turn down without

affecting the look of your lighting in order to

speed up renders.

In Review

In this chapter, we looked at lighting for both

Blender Internal and Cycles, beginning with a dis-

cussion of the different types of lamps that Blender

offers and their functional differences in Blender

Internal and Cycles. We examined different meth-

ods for dealing with shadows, both ray traced and

buffered, and explored their advantages and dis-

advantages. We also looked at Blender's World set-

tings and how they impact lighting.

For the Bat Creature, we covered creating a

three-point light setup to give dramatic flair to the

model and looked at how best to set up shadows for

characters with hair. For the Spider Bot and Jungle

Temple projects, I lit the scenes using a mix of lights

and mesh-emitter objects to create dynamically lit

scenes. When I worked with lighting in Cycles, the

Cycles render preview came in handy for getting

real-time feedback on the effect of our lights. And

even in Blender Internal, I used GLSL shading to

get some rudimentary feedback on the lighting and

shadows in the scene.

In the next chapter, we'll render the scenes

and do some final color correction and composit-

ing for our projects. I will cover render options for

both Cycles and Blender Internal and how best to

optimize render times while getting the best pos-

sible renders. We'll look at node-based compositing

using Blender's compositor, as well as creating back-

grounds and doing final tweaks in GIMP.

Make the most of shadow buffers.

The resolution

of a shadow-buffer lamp is spread out over the

lamp's cone. To make the most of it, restrict

the lamp by reducing its angle to cover only

the model (go to Size under Spot Shape in the

Object Data tab) and to make sure that you're

not wasting any of the shadow buffer's resolu-

tion on areas that aren't casting shadows.

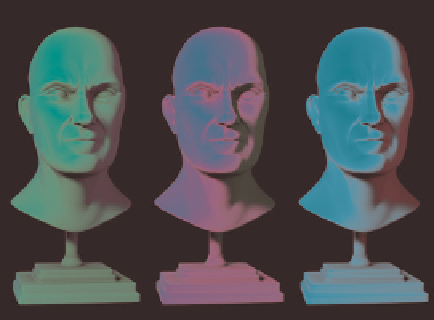

Use opposing colors.

Use color theory to your advan-

tage when lighting. Often, opposing colors (pairs

of colors on opposite sides of the color wheel,

such as orange and blue or green and purple)

work well when used as opposing key and fill

lights (see Figure 13-23). Natural light often fol-

lows this example: Sunlight is orange, while scat-

tered light from the atmosphere is blue.

Directional lighting and characters.

The direction

you choose to light a character from can change

the way it's perceived. Lighting from above often

looks regal and dignified, while lighting from

below looks scary and menacing. A few examples

are shown in Figure 13-24.

Figure 13-23: Opposing colors often make for pleas-

ant lighting schemes. Left to right: Orange key light

and a blue fill, blue key light and an orange fill,

green key light and a purple fill.

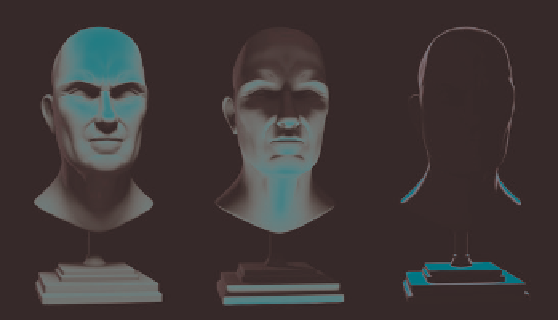

Figure 13-24: Lighting direction changes how we perceive charac-

ters. Left to right: Lighting from above looks dignified, lighting from

below looks spooky, and a rim light from behind gives an ominous

silhouette.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search