Graphics Reference

In-Depth Information

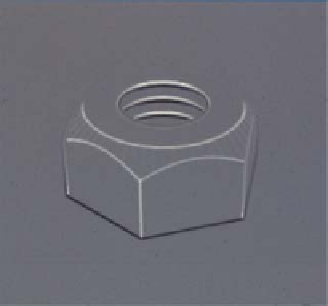

(a)

(b)

(c)

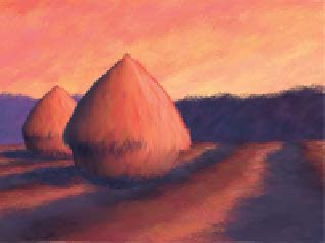

(d)

Figure 34.4: Four examples of expressive rendering. (a) Saito and Takahashi's depth-image

approach is used to enhance contours and ridges with dark and light lines, respectively.

(b) In Winkenbach and Salesin's [WS94] pen-and ink rendering, indication (the omis-

sion of repeated detail) is used to simplify the rendering of the roof and the brick walls.

(c) In the work by Markosian et al. [MKG+97], contour curves are rapidly extracted and

then assembled into longer strokes that can be stylized. (d) In Meier's painterly render-

ing work [Mei96], a back-to-front rendering of brush strokes, each attached to a point of

some object in the scene, gives excellent temporal coherence as the viewpoint is altered.

((a) Courtesy of Takafumi Saito and Tokiichiro Takahashi, ©1990 ACM, Inc. Reprinted by

permission. (b) Courtesy of David Salesin and Georges Winkenbach. ©1994 ACM, Inc.

Reprinted by permission. (c) Courtesy of the Brown Graphics Group, ©1997 ACM, Inc.

Reprinted by permission. (d) Courtesy of Barbara Meier, ©1996 ACM, Inc. Reprinted by

permission.)

While expressive rendering involves style, message, intent, and abstraction, the

first of these is particularly ill-defined, which presents a serious problem. It's used

to describe medium (“pen-and-ink style”), technique (“a stippled style”), mark-

making action (“loose and sketchy style”), mark grouping or structure (“a textured

style” or “a patterned style”), and broader notions like mood (“a film-noir style”)