Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

calves as possible over their long reproductive lifetimes. This overlooked population para-

meter—known as adult female mortality—it turns out, holds the key to understanding and

restoring populations of nearly all the world's charismatic large mammals, from whales to

grizzly bears to giant pandas to elephants, not just the one-horned rhino.

As we saw in the Amazon, the rarity of top predators is governed by the basic laws of ther-

modynamics—there simply can't be many individuals in an area that live solely on the flesh

of the larger mammals. The same principle or law should not, however, affect a plant eater

such as the one-horned rhino, which has a massive fermentation vat attached to its stomach

to digest the superabundant elephant grasses in its range. In fact, a distant relative of the one-

horned rhino was the largest land mammal that ever lived. Neither mastodon nor prehistor-

ic elephant, the heavyweight prizewinner is the extinct giant giraffe rhinoceros, as tall as a

double-decker bus and six meters long.

As a young wildlife biologist studying the one-horned rhinoceros during the reign of

Birendra, the rhino king, my first goal was to explore how large body size affected the eco-

logy and conservation of giant mammals such as the greater one-horned rhino and how it

influenced their range and abundance, our conditions of rarity. A second goal, as noted in

chapter 1, was to determine whether big plant-eating animals are passive participants or eco-

system engineers of consequence even when they occur in low numbers.

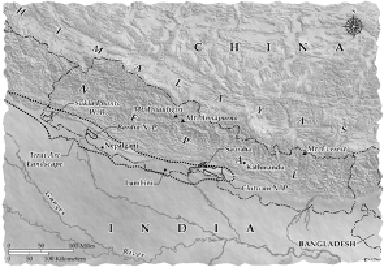

In Nepal in the mid-1980s, one-horned rhinos occurred only in Chitwan National Park,

145 kilometers southwest of Kathmandu, in the lowland jungles known collectively as the

Terai zone. After two years of trying, my colleagues and I finally received permission then

from the king of Nepal to study wild rhinos. Leading the intensive effort was a group of park

staff members, Smithsonian Institution biologists, trackers, and elephant drivers. The plan to

save these rhinos included catching them and attaching radio transmitters so we could mon-

itor their movements. The project was spearheaded by my collaborator, Hemanta Mishra, at

the time Nepal's leading wildlife biologist and a close adviser to the king.