Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

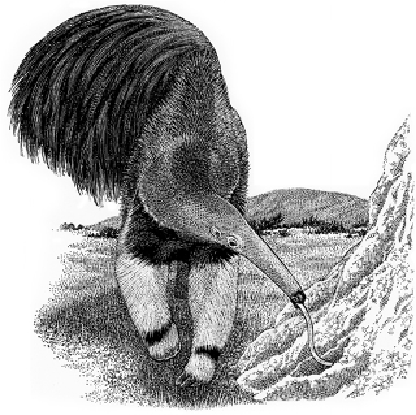

hearing, and odd gait, as defenseless against secretive jaguars and pumas. That would be a

miscalculation. With its acute sense of smell, the anteater can make up for its nearsighted-

ness. If cornered, it will stand up on its hind legs and slash with its massive claws any human

or feline predator foolish enough to tangle with it.

The mama anteater stopped and flicked her tongue in the dirt. Unlike the vast majority of

mammals, the giant anteater lacks teeth. It has no real need for them because it inserts its

long, narrow tongue into crevices, removes ants and termites with its sticky saliva, and swal-

lows them whole. Crouching downwind, I inhaled deeply to catch its scent and wondered if

consuming 30,000 ants a day gives this creature, or its flatulence, the odor of formic acid. I

smelled nothing unusual.

Edson shooed us back into the van to pursue the other goal of this outing: to search for the

Cerrado's rare endemic birds. Earlier that morning, he had led us to the Brazilian merganser,

an incredibly rare duck that, like the Kirtland's warbler and the greater onehorned rhinoceros,

is an extreme habitat specialist, one that lives only on the fast-moving, clear streams of the

upland Cerrado. Contamination from gold mining (now banned) caused the decline of this

species. Edson guided us down a canyon to give us a fabulous view of a bird whose entire

global population was probably no more than 250 individuals. Mergansers are elegant-look-

ing ducks, but the Brazilian version has a startling profile, accented by its pointy head feath-

ers. This solitary female had chicks perched on her back as she guarded them through their

first week of life.