Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

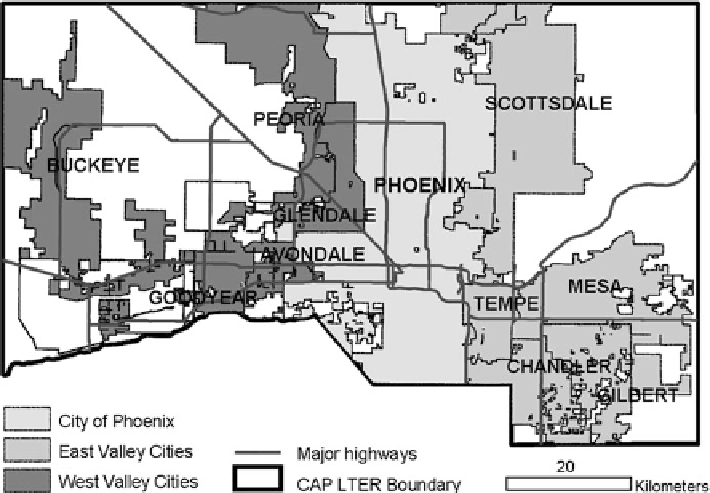

Fig. 3.1 Map of the study region with city boundaries, also noting designation of “East Valley”

and “West Valley” regions used in analyses

3.5 Why Participatory GIS?

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) has been defined many different ways and

with only a few exceptions (e.g. Harvey and Chrisman

1998

; Poore and Chrisman

2006

), these definitions focus on computing applications capable of creating,

storing, analyzing and visualizing geographic information, placing little emphasis

on the political dimensions of these processes (Dunn

2007

). In traditional GIS

methods, data precision and accuracy is a product of the quality of the record

keeping systems that generate the data set and often (in the case of mapping

exposure to toxins from smokestacks, for example) a product of the distributive

modeling choices of the researcher (Sieber

2006

). The potential to criticize the false

precision and accuracy of these mapping efforts grows exponentially as the quality

of the data set degrades (from an empirical perspective). This can contribute to a

framework for research that relies only on data sets that are easy to access and may

limit the scope of scientific inquiry as well as the types of knowledge and knowl-

edge holders that are most easily assimilated into a GIS. Often, as demonstrated in

this paper, there is a strong theoretical or applied reason to consider mapping

alternate forms of knowing or find ways to validate and improve a data set built

from diverse record keeping systems and to acknowledge the political and cultural

components of mapping efforts.