Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

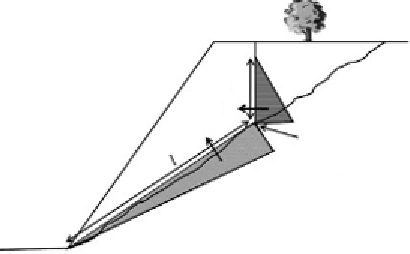

Figure 6.23

Typical model for

analysing in

uence

of water pressure

on stability of a

sliding rock slab.

z

w

V

U

Water pressure here,

P

=

z

w

×

9.8 kN/m2

Water force exerted on vertical joint,

V

=

0.5

×

z

w

×

P kN

Water uplift force on potential sliding surface

U

=

0.5

×

l

×

P kN

pressures at each location, all acting at the same time, because instru-

ments clearly showed pulses of water pressure travelling through the

slope, following a rain storm.

Even small intact rock bridges can provide suf

cient true cohe-

sion to stop seemingly hazardous slopes from failing (

Figure 5.19).

This can be a major dilemma because the rock bridges cannot be

seen or identi

ed by any realistic investigation method. Careful

geological study has failed to identify a useable link between per-

sistence and any other measurable joint characteristic (Rawnsley,

1990) and,

'

s

surface may be poor representations of characteristics inside the

unexposed mass, because of stress relief and weathering. Because of

this uncertainty, designs will typically require the risk of failure to

be minimised by incorporating toe buttresses, reinforcement with

anchorages of some kind, or some other protection, possibly using

an avalanche shelter.

From experience, wedge failures are relatively rare so that even

where these are identi

it must be remembered, traces exposed at the Earth

ed as a problem from stereographic analysis,

this might not develop in practice. Similarly, most slopes that

appear to have a toppling problem do not do so in reality, generally

because of impersistence. Care must be taken, therefore, to be

realistic in appraising the results of any geometrical analysis that

suggests there to be a problem. One factor that must be considered

is risk, which is the product of hazard (likelihood of a failure) and

consequence (likelihood of injury or damage). One other aspect is

that where major failures do occur, it is often found by later

inspection that the rock mass was in serious distress long before

failing and this might have been discovered by carefully targeted

investigation. Key factors to look for are open and in

lled joints

and distorted trees, though again the situation might be less risky

than it immediately appears

(Box 6-4)

. There is no easy answer to

this

it is a matter requiring observation, measurement, analysis,

experience and judgement, and consideration of consequence.

-