Travel Reference

In-Depth Information

lem, and reckless political opportunism in

the Anual investigation. The prime minister

could raise virtually no support against the

incipient coup d'état (although most of the

senior generals remained uncommitted to

Primo de Rivera), and Alfonso XIII made it

clear that he would not lift a finger to sup-

port his ministers. Following their inevita-

ble resignation, Alfonso welcomed the

captain general to M

ADRID

and appointed

him to head a military directorate with vir-

tually unlimited authority. Primo de Rivera

issued a public statement declaring that he

was not a dictator and that no one could

rightfully call him that. He was simply a

man whose comrades had honored him by

entrusting him with the mission of saving

the fatherland. When a journalist asked

him if he was imitating the recent fascist

seizure of power in Italy, he responded that

there was no need to copy the “great Mus-

solini.” He pointed out that there were

splendid precedents in Spanish history for

military men intervening to end corrup-

tion and mismanagement by politicians.

He spoke of nine men who would accom-

plish as much as possible in 90 days, a

seeming promise of limited disruption of

constitutional norms that did much to

reassure the public.

The regime of Primo de Rivera did in fact

turn out to be a dictatorship, and it lasted

for years rather than months. Although the

military directorate was broadened to

include civilian members in 1925, the con-

stitution of 1876 was essentially discarded,

solved. Under the royal mandate Primo de

Rivera ruled by decree, just as despotically

as any contemporary dictator. Yet by com-

parison with most of them he was moder-

ate in his tactics. There was little of the

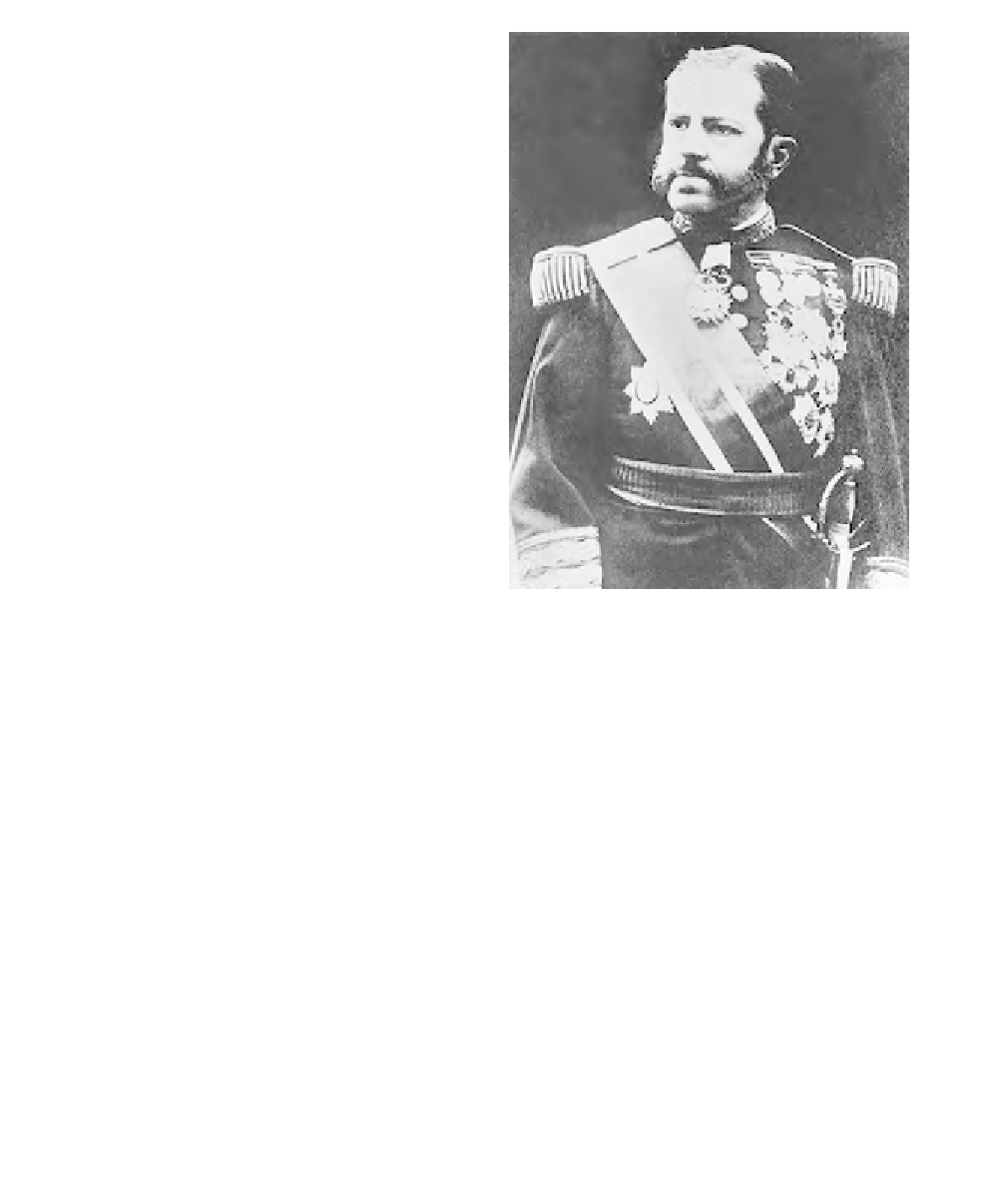

General Miguel Primo de Rivera

(Library of Congress)

brutality and persecution of dissidents that

characterized, for instance, the Franco tyr-

anny in later decades, to say nothing of

those in Russia and Germany. Moreover

many of his early programs were construc-

tive. His termination of the war in M

OROCCO

in 1926 was praised by some as a sensible

compromise between imperialism and

abandonment, even though it disappointed

some of his hard-line military colleagues.

True to his oft-repeated pledge, he attacked

bureaucratic waste and corruption while

seeking to root out the traditional power of

the caciques (local political bosses linked to

the major parties). He pursued a course of

modernization aimed at rendering the

Search WWH ::

Custom Search