Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

storage are too expensive, sweet potato roots rarely keep

for more than 2-3 weeks (Rees

et al

. 2001, Tomlins

et al

.

2002). In this case a wide range in keeping quality of

different varieties has been observed, and one approach to

extending shelf life would be the introduction of cultivars

with better keeping qualities, an approach that would cause

no additional cost to farmers and traders (Rees

et al

. 2003).

In-ground storage is practiced, but not as widely as for

cassava. The main problem is that at the onset of the dry

season infestation by the sweet potato weevil (

Cylas

spp)

becomes significant and damages the crop (see below).

Traditional storage technologies for sweet potato roots

have been reported in tropical countries such as Bangladesh

(Jenkins 1982), India (Prasad

et al

. 1981, Ray & Ravi 2005),

Tanzania (Tomlins

et al

. 2007) and Kenya (Karuri & Ojijo

1994, Karuri & Hagenimana 1995). The success of these

storage technologies, however, has been variable (Ray &

Ravi 2005). A review of storage methods (Ray & Ravi 2005)

has highlighted the need for further assessment of the factors

affecting storage because an understanding of these factors

remains incomplete. In Tanzania, a study located at

a research station investigated stores that varied by store type

(pit or heap), cultivar and ventilation by measuring O

2

and

CO

2

levels, relative humidity, temperature, root condition

and weight loss (Van Oirschot

et al

. 2007). The findings

indicated that the main factors that improved storability of

fresh sweet potato under tropical conditions were the use of

good-quality roots free of damage and disease, not lining the

stores with grass, and avoiding temperature build-up in the

stores. The type of store (pit or heap), cultivar and ventila-

tion were all found to have minimal effect on root keeping

qualities. The study concluded that fresh roots could be

stored for up to 12 weeks and that, by this time, stored roots

may taste sweeter than freshly harvested ones (Tomlins

et al

.

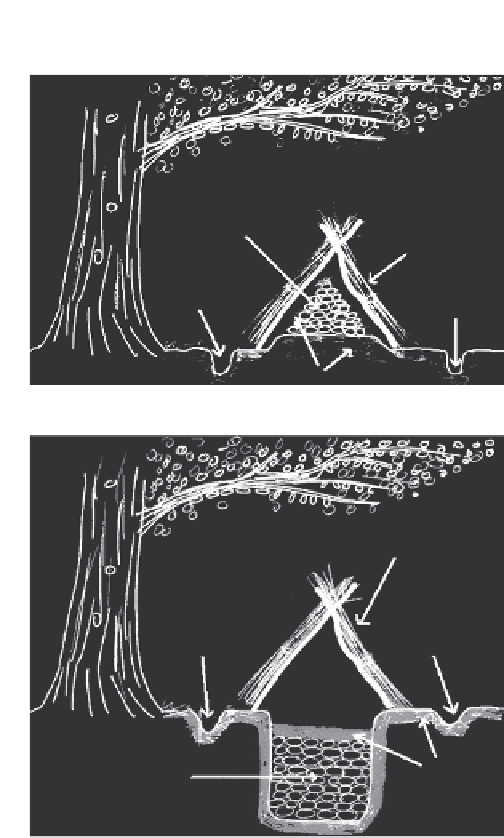

2007). The design of two stores that were tested in Tanzania

are shown in Figure 18.5.

(a)

Heap store

SHADE

Sweetpotatoes

Roof

Drainage

channel

Drainage

channel

Soil

(b)

Pit store

SHADE

Roof

Drainage

channel

Drainage

channel

Soil

Sweetpotatoes

Figure 18.5

Construction of heap and pit stores in

the Lake Zone of Tanzania.

snack products (Owori & Agona 2003). Substitution of

wheat flour, either with fresh, grated roots or sweet potato

flour, is gaining a foothold in the snack product market in

Kenya and Uganda and bread containing biofortified sweet

potato in Mozambique (Tomlins

et al

. 2009). Promotion of

commercial processing of primary products would increase

the utilization of sweet potato flour as an ingredient in

snack product processing. There is great variation in the

processing characteristics of sweet potato cultivars but

generally dry matter is an important characteristic.

While many new sweet potato products have been

developed in Africa, the priority is still predominantly in the

improvement of the quality of the flour after drying and stor-

age (van Hal 2000). Recent initiatives have focused on the

Processing of sweet potato

In countries where sweet potato is a staple, one strategy to

ensure the availability of sufficient food, especially during

the lean seasons and where sweet potato cultivation is lim-

ited to only one season in a year, is to process the roots into

dried chips and store them in this form (Owori & Agona

2003). The dried chips are either reconstituted by boiling

or are ground into flour which may or may not be mixed

with millet/sorghum flour for making porridge. Sweet

potato processing for human consumption in many

countries is not yet commercialized. Studies in some coun-

tries have, however, investigated the feasibility of sweet

potato as a partial substitute for imported wheat flour in