Game Development Reference

In-Depth Information

using all

of our available senses repeatedly. What is important about

this in terms of games is that not only will single-ire flashcards not

suffice in providing information to players, the fact that they are often

presented in a visual-only

fashion is absolutely not sufficient to pro-

mote learning. The Attentional Control Theory diagram in Figure 3.2

should illustrate some of these concepts more clearly. Think of the

eyes on the right side and the ears on the left. The area in which you

store information you have just seen or heard is known as your execu-

tive controller

*

and is referred to in the diagram.

If we think of the human brain as a computer for a moment, a few

key portions are addressed in learning that we have discussed here.

The first and perhaps most important is long-term memory, which

is made up of crystallized intelligence in the form of schema. Long-

term memory is kind of like a computer's hard disk drive. Then, of

course, we have the RAM, which corresponds to short-term memory.

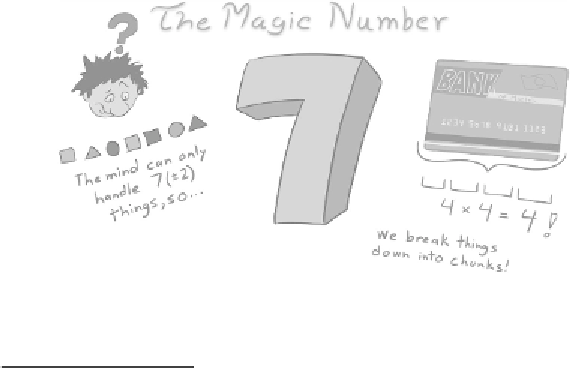

We can hold about seven things in our short-term memory at any

given moment, so we desperately need a RAM upgrade. We solve

this RAM limitation by chunking things into groups that are smaller

than 7 (see Figure 3.3).

What's interesting about our RAM-like working memory

is that

despite it having been tested repeatedly to be 7 ± 2 items,

†

putting in

Figure 3.3

Magic number diagram. (Figure courtesy of Peter Kalmar.)

*

This is a component of Alan Baddeley's

Working Memory

theor y.

†

Miller, G. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our

capacity for processing information.

Psychological Review

, 63.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search