Game Development Reference

In-Depth Information

Like the dog trainer analogy, we often make a critical mistake when

making games or activities for our players; namely, players don't come

with predestined knowledge of how to play your game, nor do pup-

pies come housebroken

.

In the current games industry, we have been

spoiled. We have a large demographic of players who have knowledge

of something called

genre

. This might be your first time reading some-

thing based in cognitive psychology, or you might read on the topic

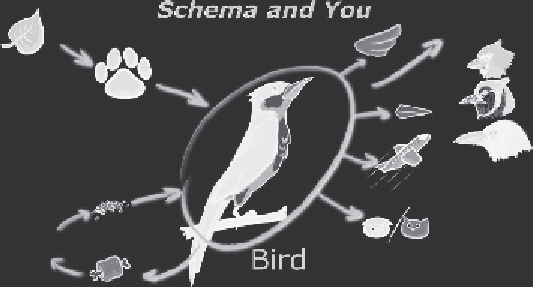

all the time. In either case, we as humans have a habit of categorizing

things through something called a

schema

. We sort things so that our

minds can easily manage them. A sparrow is a sort of bird, which

is a sort of animal, which is a sort of living thing, and so on. With

these schema distinctions, we associate

rules

. Birds can be fed, for

example. The bottom line that we tend to miss is that we had to learn

these schemas at some point. Just like game players know that shoot-

ers often have a reload button, we know that birds will often fly away

when approached. The important distinction we often miss, however,

is that both gamers and children had to learn these from someone, or

something, at some point in their lives. The sort of organization the

mind undertakes can be seen in Figure 1.1.

In the childhood of individuals who grew up alongside the games

industry, like me and many other people born between 1965 and 1990,

games taught us by starting with simple controls. We cut our teeth on

the Atari 2600™ with its one button before gradually moving on to

the NES with two, the SNES with six, and so on. We learned simple

controls like moving objects on the screen in games like

Pac- Man

™,

Colors

Wings

Ca

rdinal

Life

Beak

Blue Jay

Animal

Crow

Flies

e mind

stores

data in an

organized

way.

Food

Wild/Pet

Figure 1.1

Schema diagram. (Figure courtesy of Peter Kalmar.)

Search WWH ::

Custom Search