Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

A

B

C

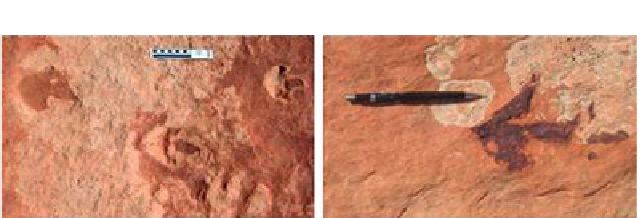

FIGURE 4

Trace fossils in ancient inland erg deposits. (A, B) Vertebrate trace fossils in the Lower

Jurassic Navajo Sandstone, near Coyote Buttes in Kane County, Utah (photographs courtesy of

Marjorie A. Chan). Small, three-toed, dinosaur tracks in concave epirelief (A, scale

¼

10 cm),

and small, three-toed, dinosaur track that has been replaced by dark brown iron oxide (B, pen-

cil

¼

15 cm long). (C) Large, three-toed, dinosaur track in concave epirelief in the Lower Jurassic

Navajo Sandstone, in the San Rafael Swell in Emery County, Utah (shoe

¼

30 cm long).

in the Lower Jurassic Navajo Sandstone in southern Utah. He demonstrated that

the tracks (

Grallator

and

Brasilichnium

) were emplaced deeply in dry sand and

subsequently buried by thin grain-flow avalanches on the dune foresets. His anal-

ysis suggests not only that Jurassic vertebrates commonly walked on the steeply

dipping lee side of dunes but also that their tracks on that side had a high preser-

vation potential. This conclusion effectively contradicts earlier assumptions by

previous workers that the steep angles of repose and cohesion-less sand grains

of dune slip faces generally precluded good preservation of tracks.

In the Middle Jurassic Entrada Sandstone in southern Utah,

Mil`n and

Loope (2007)

examined large numbers of three-toed theropod dinosaur tracks

(

Megalosauripus

and

Therangospodus

) in various preservation states, resulting

from variations in the gait of the dinosaurs and a range of paleoslopes of the

Search WWH ::

Custom Search