Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

individually distinct and identifiable trace fossils cannot be observed. The

parallel concept of

ichnofacies

, introduced by

Seilacher (1964, 1967)

,isan

extension of the biofacies approach by recognizing recurrent associations of

ichnotaxa that represent particular paleoenvironments or specific sets of envi-

ronmental conditions, such as bathymetry, salinity, substrate consistency, etc.

(

MacEachern et al., 2012

). In contrast to ichnofacies, ichnofabric extends

beyond a simple listing of common associations of ichnotaxa by highlighting

the broader effects of organism behavior on the substrate itself.

In the first formal use of the term “ichnofabric” in a refereed publication,

Ekdale and Bromley (1983)

exemplified the concept by illustrating in great

detail the ichnofabric of the 15-cm-thick Kjølby G

˚

rd Marl, a thoroughly bio-

turbated marly chalk layer in the uppermost Cretaceous of western Denmark.

They wrote that ichnofabric includes “those aspects of the texture and internal

structure of the bed resulting from all phases of bioturbation” (

Ekdale and

Bromley, 1983

: 110). In the glossary of an SEPM short course text on ichnology,

they further defined ichnofabric as “all aspects of the texture and internal struc-

ture of a sediment that result from bioturbation and bioerosion at all

scales; includes both bioturbation fabric and bioerosion fabric” (

Ekdale et al.,

1984a

: 308).

From that point, the practical application of the ichnofabric concept ramified

in several different, complementary directions. Some ichnofabrics may be

thought of as

simple ichnofabrics

in cases where they contain just one type

of trace fossil. In certain cases, the ichnofabric consists of a single ichnotaxon

superimposed on primary stratification with portions of the original sedimen-

tary laminae still discernible behind the trace fossils (

Fig. 1

). In other cases,

the entire bed is totally bioturbated with only a single ichnotaxon evident in

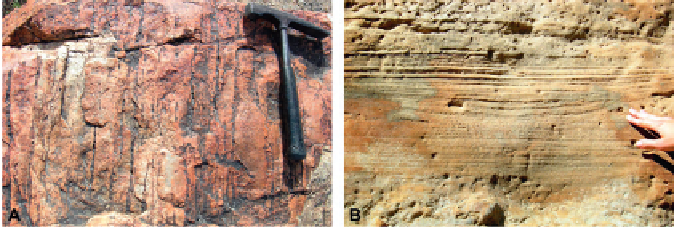

FIGURE 1

Monoichnospecific ichnofabrics in incompletely bioturbated sediment, as depicted in

these two examples, often reflect high-energy depositional environments, such as intertidal settings

(as in A) or storm-related deposits (as in B). In such situations, the interplay of sedimentation, bio-

turbation, and erosional processes is directly reflected in the resultant ichnofabrics. (A)

Skolithos

ichnofabric in the Watson Ranch Quartzite, Lower Ordovician, Confusion Range, Millard County,

Utah. (B)

Ophiomorpha

ichnofabric alternating with low-angle, cross-stratified beds in a “lam-

scram” succession (after

Ekdale, 1985a

) in the Blackhawk Formation, Upper Cretaceous, Wasatch

Plateau, Carbon County, Utah.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search