Graphics Reference

In-Depth Information

seldom collide. The shifting of the flock is a result of a bird mimicking a shift

in movement to another bird in the flock; the slight delay in movement sends

a wave through the flock. Studies of flocks using high-speed cameras have

suggested that individual members of a flock are influenced by the nearest 5

to 10 of the bird's neighbors, with the emphasis being placed on neighbors to

either side of the bird rather than those either in front or behind. This may have

something to do with the field of vision of the kinds of birds that tend to flock.

Studies using humans identified that shifts in the direction of groups that have

very similar patterns to flocking birds are determined by the movement of

around 5% of the group, at which point the remainder of the group will follow.

Some groups of birds such as crows and rooks form clans. Other birds form

bonds that last a lifetime; for example, swans are said to mate for life, though for

some birds multiple breeding partners offers a better solution. The female hedge

sparrow or dunnock is one such that chooses to mate with a number of males.

Bird flocking is also very useful during migration. Martins and sparrows gather

together in northern Europe around the end of September to mid-October

each year. This gathering might assist with navigational aspects of long-distance

travel, though for some animals flying together offers energy-efficiency gains.

It has been observed that swarming locusts will fly in loose formations and

synchronize their wing beats to reduce turbulence and assist in their flight.

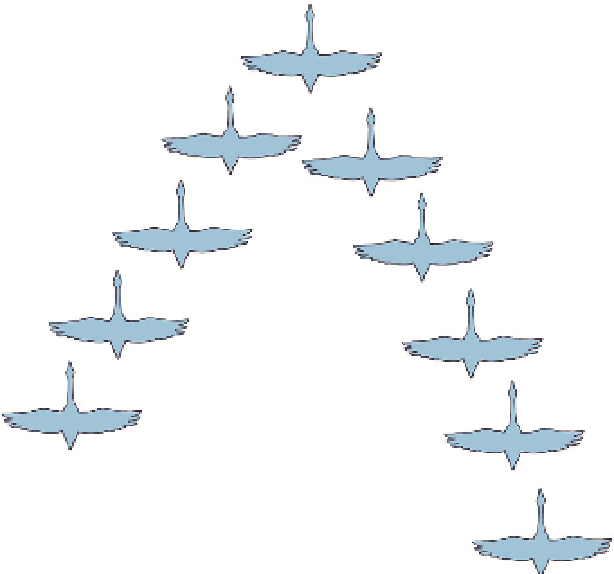

Flying in more formal formations may also produce increased efficiencies. For

a bird flying behind and slightly to one side of the lead bird, the turbulence

created during flight may offer additional lift because the greatest turbulence

FIG 4.62

Geese flying in formation

minimizes the drag on the birds flying

in the wake of the leading birds.