Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

sublayer is missing and is replaced by a viscous sublayer. The wave sublayer is

approximately five wave heights deep and the constant-flux sublayer depth depends

on the surface roughness, too.

At the top of unstably stratified marine boundary layers rolls and cellular con-

vection patterns can develop. Since the detection and monitoring of these cloud

features is beyond the present abilities of ground-based remote sensing, they are not

addressed further here.

Overviews of air-sea interaction, the drag forces exerted on the marine boundary

layer, and detailed discussions of momentum transfer between the sea surface and

the air above may be found in Donelan (

1990

), Banner and Peirson (

1998

), and

Foreman and Emeis (

2010

). Sullivan and McWilliams (

2010

) discuss the coupling

processes between surface gravity waves and adjacent winds and currents in the

turbulent boundary layers of the atmosphere and the ocean.

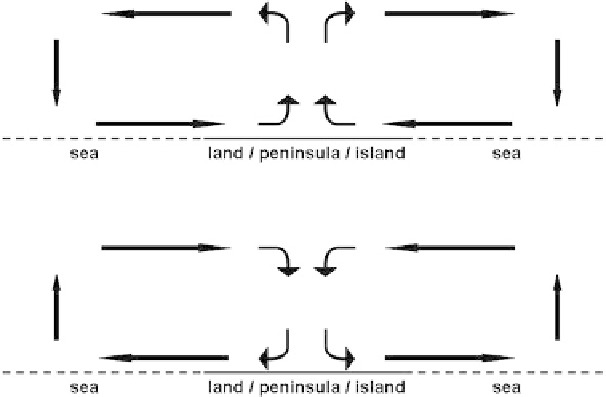

2.5.1 Land-Sea Wind System

Due to the different thermal inertia of land and sea surfaces, secondary circulation

systems - land-sea wind systems - can form at the shores of oceans and larger lakes,

which modify the ABL structure. Under clear-sky conditions and low to moderate

winds, land surfaces become cooler than the adjacent water surface due to long-

wave emittance at night and they become warmer than the water surface due to

the absorption of short-wave irradiance during daytime. As a consequence, rising

motion occurs over the warmer and sinking motion over the cooler surfaces. A flow

from the cool surface towards the warm surface develops near the surface and a

Fig. 2.9

Schematic presentation of a height cross-section of a land-sea breeze system during

daytime (

top

) and night-time (

below

)

Search WWH ::

Custom Search