Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

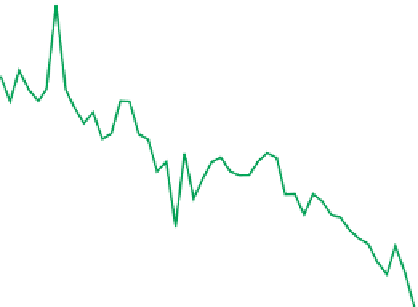

FIGURE 15.2

Annual,

volume-weighted hydrogen-ion

concentration in bulk precipita-

tion at the Hubbard Brook

Experimental Forest, NH. The

line represents a linear regres-

sion at p

PRECIPITATION TRENDS

100

90

80

,

0.05.

(Updated

70

from

Likens 2006

.

)

60

50

40

30

20

10

1960

1965

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

2015

Water year

polluted (

Figure 15.2

). Studies of ice cores from glaciers in Greenland and elsewhere and

paleoecological analyses of lake sediments have also shown these historical changes in

precipitation chemistry.

In the early 1980s we began to study cloud- and fog-water chemistry, and found that it

could be especially polluted, even more so than rain at a specific site, and that acidic fog

events could be regional in extent (

Weathers et al. 1988

). One fog event collected near Bar

Harbor, ME, was black in color and had a pH of 2.42 (

Weathers et al. 1988

).

In addition to increasing emissions of SO

2

and NO

X

with growing industrialization after

World War II, another major factor affecting the regional pollution of the atmosphere and of

precipitation was that during the 1950s the heights of chimneys and smokestacks increased

dramatically (

Likens 1984, 1991

) carrying pollutants higher into the atmosphere, thereby

reducing local pollution at ground level, but enhancing the potential for long-distance

transport of pollutants in the atmosphere, affecting regions distant from the pollutant

source. Indeed, SO

2

and NO

X

can be transported in the atmosphere for thousands of

kilometers, allowing acid rain to cross political boundaries and impact ecosystems far

downwind from where these acid precursors are generated and emitted. This transfer of

pollutants through the atmosphere became highly charged politically, and ultimately led to

regulations controlling emissions in the United States (1990 Clean Air Act Amendments),

Canada, and Europe (see

Likens 2010

).

There are numerous ecological effects of acid rain on natural ecosystems, but they are

greatly complicated by diverse abiotic and biotic interactions and ecosystem impacts (e.g.,

Driscoll et al. 2001

). For example, acid rain can mobilize aluminum from the soil. When

aluminum is bound in minerals of the soil, it is harmless to biota, but in the dissolved

form it can be very toxic. Likewise, acid rain can leach calcium and magnesium from the

soil, thereby reducing the buffering capacity of the soil (

Likens et al. 1996, 1998; Likens