Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

example that corn could be easily reproduced asexually

(i.e. say through apomixis), then there would be no need

to develop hybrid corn cultivars because the highly het-

erozygous nature of a hybrid line could be “genetically

fixed” and exploited through asexual reproduction.

The process of developing a clonal cultivar is, in

principle, very simple. Breeders generate segregating

progenies of seedlings, select the most productive geno-

typic combination and simply multiply asexually, this

also stabilizes the genetic make-up (i.e. avoids problems

relating to genetic segregation arising from meiosis).

Despite the apparent simplicity of clonal breeding it

should be noted that while clonal breeders have shared

in some outstanding successes, it has rarely been due to

such a simple process, as will be noted from the example

below.

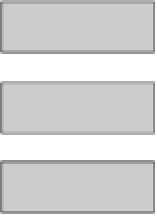

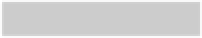

250 -300 crosses

140 000 seedlings

140 000 single plants

4 000

×

3 plant plots

1 000

×

12 plants

1 000

×

6 plants

500

×

12 plants

500

×

20 plants

Outline of a potato breeding scheme

200

×

12 plants

200

×

100 plants

The breeding scheme that was in use at the Scottish

Crop Research Institute prior to 1987 is illustrated in

Figure 4.8. It should be noted that the programme used

two contrasting growing environments. The

seed site

(indicated by grey boxes) was located at high altitude

and was always planted later and harvested earlier than

would be considered normal for a typical

ware crop

(indicated by black boxes), in order to minimize prob-

lems of insect borne virus disease infection. A ware crop

is the crop that is produced for consumption rather than

for re-planting.

Each year between 250-300 cross pollinations were

carried out between chosen parents. From each cross

combination the aim was to produce around 500 seeds,

leading to 140 000 seedlings being raised in small pots

grown in a greenhouse (two greenhouse seasons were

needed to accommodate the 140 000 total). At harvest,

the soil from each pot was removed and the tubers pro-

duced by each seedling were placed into the now empty

pots. At this stage a breeder would visually inspect

the small tubers in each pot (each seedling being a

unique genotype) and either select or reject each one.

One tuber was taken from amongst the tubers pro-

duced by the selected seedlings, while all tubers from

rejected clones were discarded. The seedling genera-

tion, as in most clonal crops, in the greenhouse was

the one and only generation that derived directly from

true botanical seeds

(i.e. from sexual reproduction). All

Figure 4.8

Potato breeding scheme used at the Scottish

Crop Research Institute prior to 1987.

other generations in the programme were by vegetative

(clonal) reproduction, in other words from tubers.

The following year the single selected tubers (approx-

imately 40 000) were planted in the field at the '

seed

site

' as single plants within progeny blocks. This stage

was referred to as the first clonal year. At harvest each

plant was harvested, by hand digging, and the tubers

exposed on the soil surface in a separate group for

each individual plant. A breeder would then visually

inspect the produce from each plant and decide, on that

basis, to reject or select each group of tubers (i.e. each

clone). Three tubers are retained from '

the most desir-

able

' plants and planted in the field at the same seed

site in the following year (the second clonal year) as a

three plant, un-replicated plots. First and second clonal

year evaluations were therefore carried out under seed

site conditions to reduce as far as possible the chances

of contamination, especially by virus diseases.

Second clonal year plots were harvested mechanically

and, again, tubers from each plot exposed on the soil

surface. A breeder examined the tubers produced and

decided to select or reject each clone, again on the basis

of visual inspection. Tubers from selected clones were