Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

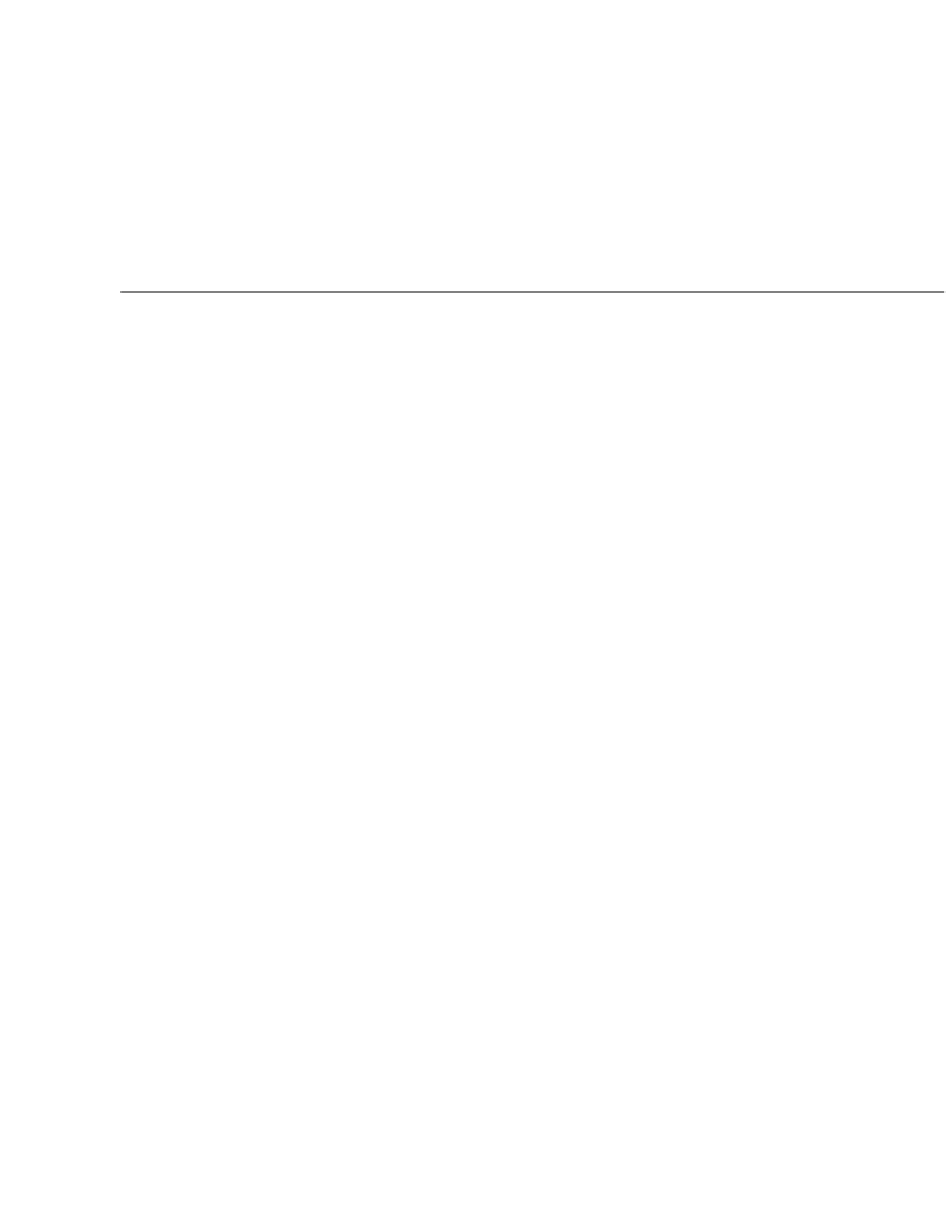

Table 4.1

Shifts in the Conceptualization of Computer User Over Time

Who Is the User?

Scope of Work

Technology

Systems Support

Individual

Worker-based

Terminal or personal computer

Decision support systems (DSS)

Group

Team-based

Networked computers

Group systems (GDSS, GSS)

Organization

Distributed work

Web-based platforms;

Enterprise-wide systems

multimedia

(e.g., EIS)

Community

Globalization

Ubiquitous computing

Electronic commerce, online

forums, and communities

quality and efficiency of user decision processes, and user perceptions of the technology. In the

early days of organizational computing, designers attempted to accommodate variations in user

preferences where possible, but for the most part users were treated as common collectives.

Indeed, individual differences and their implications for design were not center stage in systems

design for several decades; research focused instead on designing technology to fit work task

demands and assuring user motivation and acceptance (e.g., see Huber, 1983).

Though not to be underestimated, this relatively confined world of HCI was a comforting setting

for systems designers and IS researchers until collaborative systems (i.e., groupware) came along.

Suddenly the user became the group, tasks became multi-party, and decision processes became

entwined with computer-mediated communication systems (Applegate, 1991; Gray and Olfman,

1989; Hiltz and Turoff, 1981; Olson and Olson, 1991). So-called advanced information technologies

offered the potential to dramatically impact the social dynamics of organizational life (Huber, 1990;

Rice, 1992). The complexity of the HCI setting increased dramatically. Systems designers and IS

researchers, with their roots in psychology and organizational behavior, quickly became students of

organizational communication and sociology. Issues of collaboration, coherence, conflict manage-

ment, group decision processes, and so on, were added to the more traditional HCI concerns (e.g.,

Jessup and Valacich, 1993; Galegher, Kraut, and Egido, 1990; Malone and Crowston, 1994).

Today we are witness to a further explosion in the complexity of HCI as information systems are

developed to support dynamic groups and communities, and work moves across the traditional

boundaries of task, locale, and corporation. On the surface it may be the individual who types, talks,

and looks at a computing device; but the presence and participation of others is near omnipresent.

Further, the parties involved and nature of the work that people are doing together via computer is

likely not fully specified. Groups are scattered and transient. Tasks are murky, and the organizational

context is a shifting ground of business units, partners, or other entities—not all of which are com-

pletely clear or known. In sum, we are witness to a confluence of changes in technology and the

nature of work that are expanding our notion of “user” and the essentials of human-computer inter-

action. Computers may be easier to use today than in the past, in the sense that machines are more

intelligent and interfaces are more multimedia-based and friendly; however, human-computer sys-

tems are also more challenging to design, because they must accommodate collections of people

from a multitude of backgrounds with diverse personal and professional needs who are interacting

across organizational, geographic, and task boundaries. Thus, today we are witness to a profound

expansion in the scope of HCI design and an explosion in the mandate for HCI research. Table 4.1

summarizes how the conceptualization of computer user in HCI design has broadened over time.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search