Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

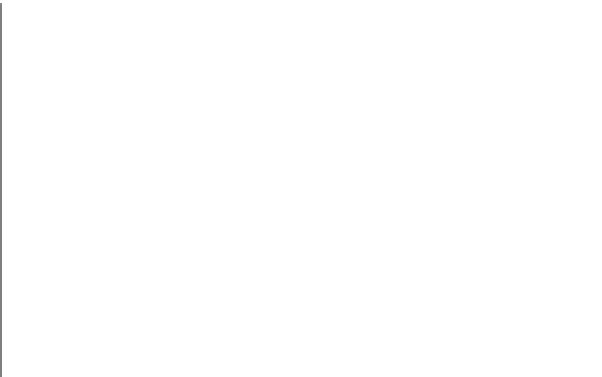

100%

0%

Infected

Unwell

Consult

G.P.

Notified as

“Food-

poisoning”

Sample

taken

Pathogen

found

Reported to

surveillance

system

Figure 12.1

Surveillance for food-borne illness.

Laboratory reports of enteric infections

Routine reporting from medical laboratories gives a

useful picture of the importance of pathogens present

in the population. It does, of course, only record the

results from

samples

actually submitted to laboratories

and can therefore be distorted by any factors which

might influence sampling, for example, increased

media attention. Results can also be influenced by the

likely success of identifying a pathogen when present,

and this success may change as laboratory methodolo-

gies improve. For example, during the 1980s, better

techniques for the recovery of

Campylobacter

spp.

became routinely available, and this undoubtedly

contributed to the overall increase in numbers reported

during the 1980s and 1990s. However, since the early

1990s, methods have been standardised and should

not be the explanation for the continuing increase for

Campylobacter

spp., 200,000 reported EU cases in

2010.

Other extraneous events also play a part when iden-

tifying laboratory-confirmed cases. A change in policy

occurred when the Advisory Committee on the

Microbiological Safety of Food recommended in 1995

that

all

stool samples be screened for

Escherichia coli

O157. Previously, many laboratories were selective and

had perhaps restricted the examination for this organ-

ism to stools from children or from patients with

bloody diarrhoea.

The variation in laboratory methods and sample

submissions may partly explain the geographical differ-

ences seen throughout the United Kingdom.

infectious causes of food poisoning. It is estimated that

only between 1 and 10% of all food-borne illness is even

counted by the various surveillance systems, and this

varies from cause to cause (Fig. 12.1).

In any population, not all of those who become infected

become ill. Of those who are unwell, only a proportion

will seek medical help and can be counted as 'notifica-

tions. Those who do not require medical assistance are not

included in any surveillance system. If the clinician sus-

pects 'food poisoning, then that patient

may

be formally

notified, for which the GP will receive a notification fee.

The number of notifications may be supplemented, for

example, Health Officials and Environmental Health

Officers in the United Kingdom, including cases they

become aware of during their investigation. The doctor

may submit appropriate samples for laboratory investiga-

tion, and this forms the basis of laboratory surveillance.

The sample taken may affect the result; for example, vomi-

tus is more appropriate for a viral agent than is a stool

sample. Unless the sample is submitted within 24 hours of

onset of illness, a viral cause is likely to be missed. If a

pathogen is identified, then the result should be recorded

by the laboratory surveillance. When no pathogen is iden-

tified, it does not, of course, mean that none were present

but rather that the laboratory did not identify anything.

This will depend on the organisms under scrutiny. When

an outbreak occurs, it is likely that there will be greater

investigation of the source of infection than might be the

case when only a single patient is unwell. Causes of

outbreaks may be different from the causes of sporadic

infections, and it may not be possible to extrapolate.