Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

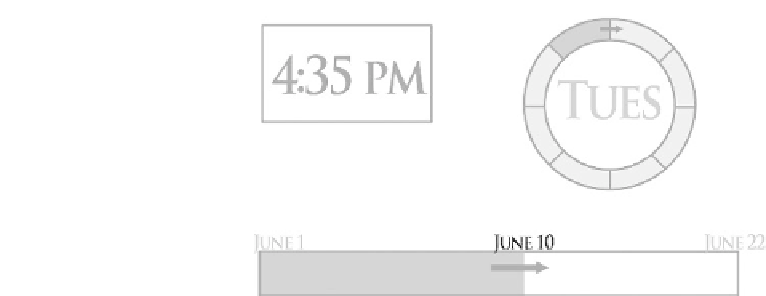

Figure 4.2

The three most common kinds of temporal legend - digital clock, cyclical and bar. The

graphical cyclic and bar legend can communicate at a glance both the specific instance and the

relation of that moment to the whole (source: M. Harrower)

(the finest temporal unit resolvable) and pace (the amount of change per unit time). Pace

should not to be confused with frames-per-second (fps): an animation can have a high frame

rate (30 fps) and display little or no change (slow pace). Perceptually, true animation occurs

when the individual frames of the map/movie no longer are discernable as discrete images.

This occurs above roughly 24 fps - the standard frame rate of celluloid film - although

frames rates as low as five fps can generate a passable animation effect. Higher frame rates

yield smoother looking animations, although modest computers will have trouble playing

movies at high frame rates, especially if the map is a large raster file.

The passage of time or the temporal scale is typically visualized along side the map

animation through a 'temporal legend'. Figure 4.2 shows three different kinds of temporal

legend: digital clock, cyclical time wheel and linear bar. The advantage of graphical temporal

legends, such as the time wheel and linear bar, is that they can communicate at a glance

both the current moment (e.g. 4:35 p.m.) and the relation of that moment to the entire

dataset (e.g. halfway through the animation). Because it is often assumed that these kinds

of legends support different map-reading tasks, designers often include more than one

on a single map. Cyclic legends, for example, can foster understanding of repeated cycles

(e.g. diurnal or seasonal), while linear bars may emphasize overall change from beginning

to end.

By making a temporal legend interactive, the reader can directly manipulate the playback

direction and pace of the movie, or jump to a new moment in the animation (known as

non-linear navigation). This has become a common interface action in digital music and

video players and many map readers now expect to be able to directly interact with temporal

legends to control the map. One unresolved problem with legend design is split attention:

because animated maps, by their very nature, change constantly, the moment the reader

must focus on the temporal legend they are no longer focusing on the map and may miss

important cues or information. If they pause the animation to look at the legend, they lose

the animation effect. The more the reader must shift their attention between the map and

the legend, the greater the potential for disorientation or misunderstanding. Proposed but

untested solutions to the problem of split attention include (1) audio temporal legends

and (2) embedded temporal legends that are visually superimposed onto the map itself.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search