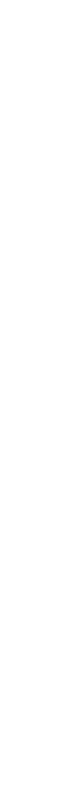

Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

20°

10°

SUDANO - SAHELIAN AFRICA

SUB-HUMID

AND

MOUNTAIN

EAST AFRICA

HUMID AND SUB-HUMID

WEST AFRICA

SUDANO -

SAHELIAN

AFRICA

HUMID

CENTRAL

AFRICA

ATLANTIC

0°

0°

OCEAN

INDIAN

OCEAN

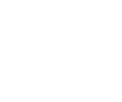

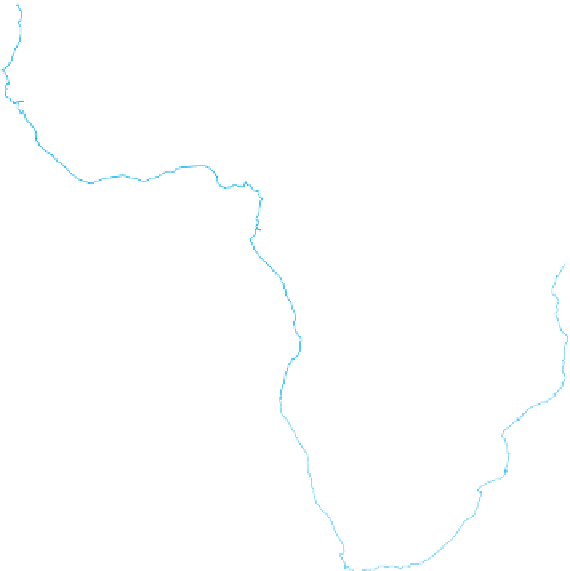

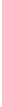

Figure 13.21

Major Regions and Forest Zones in

Subsaharan Africa.

This map is based

on a fi gure in a World Bank technical

paper on the forest sector in Subsaharan

Africa. The map shows major forest

regions crossing state boundaries, but

planning regions adhere to state bound-

aries.

Adapted with permission from:

N.

P. Sharma, S. Rietbergen, C. R. Heimo,

and J. Patel. A Strategy for the Forest

Sector in Sub-Saharan Africa, World Bank

Technical Paper No. 251, Africa Technical

Department Series (Washington, DC: The

World Bank, 1994).

10°

0°

SUBSAHARAN

AFRICAN FOREST

10

°

Tropical rainforest

SUB-HUMID AND SEMI-ARID

SOUTHERN AFRICA

SUB-HUMID

AND

MOUNTAIN

EAST AFRICA

Tropical deciduous forest

20°

Tropical dry forest

None, or limited forest

Boundaries of planning

regions

30°

0

400

800

1200 Kilometers

Longitude East of Greenwich

0

400

800 Miles

10˚

0˚

10°

20°

30°

40°

50°

Biological Diversity

International concern over the loss of species led to calls

for a global convention (agreement) as early as 1981. By

the beginning of the 1990s, a group working under the

auspices of the United Nations Environment Program

reached agreement on the wording of the convention, and

it was submitted to UNCED for approval. It went into

effect in late 1993; as of 2011, 168 countries had signed

it. The convention calls for establishing a system of pro-

tected areas and a coordinated set of national and inter-

national regulations on activities that can have signifi cant

negative impacts on biodiversity. It also provides funding

for developing countries that are trying to meet the terms

of the convention.

The biodiversity convention is a step forward in

that it both affi rms the vital signifi cance of preserving

biological diversity and provides a framework for coop-

eration toward that end. However, the agreement has

proved diffi cult to implement. In particular, there is an

ongoing struggle to fi nd a balance between the need of

poorer countries to promote local economic development

in all sorts of ways. Take the case of the GEF. Between

1991 and 2010, the GEF provided $4.5 billion in grants,

primarily to projects involving climate change or biodi-

versity. Even though the GEF is charged with protecting

key elements of the global environment, it still functions

in a state-based world, as suggested by Figure 13.21—a

map from a 1994 World Bank technical report on the

forest sector in Subsaharan Africa that divides the realm

into “major regions” that follow state, rather than ecologi-

cal borders. Moreover, the GEF nonetheless serves the

important role of providing fi nancial resources to four

major international conventions on the environment: the

Convention on Biological Diversity, the United Nations

Framework Convention on Climate Change, the United

Nations Convention to Combat Desertifi cation, and the

Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants.

A few global environmental issues are so press-

ing that efforts are being made to draw up guidelines for

action in the form of international conventions or treaties.

The most prominent examples are in the areas of biologi-

cal diversity, protection of the ozone layer, and global

climate change.