Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

Delta

KAZAKHSTAN

KAZAKHSTAN

KAZAKHSTAN

UZBEKISTAN

UZBEKISTAN

UZBEKISTAN

0

100

160 Km

100 Miles

0

100

160 Km

100 Miles

0

100

160 Km

100 Miles

0

0

0

A

B

C

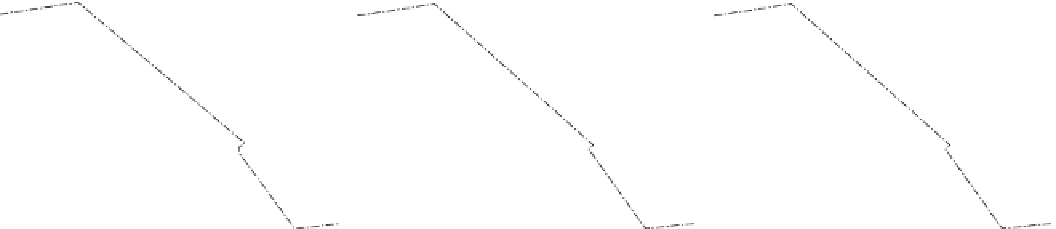

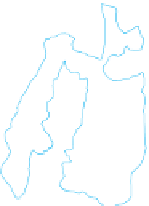

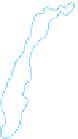

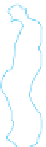

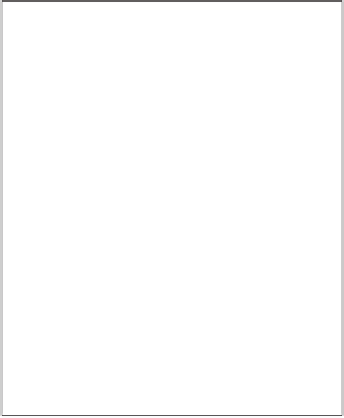

Aral Sea, mid-1960s

Aral Sea, early 2000s

Aral Sea, 2011

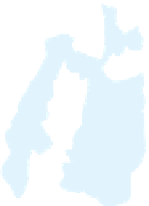

Figure 13.9

The Aral Sea.

Affected by climatic cycles and affl icted by human interference, the Aral Sea

on the border of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan has shrunk. In a quarter of a century, it lost three-

quarters of its surface area.

© E. H. Fouberg, A. B. Murphy, H. J. de Blij, and John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

distribution is sustained through the

hydrologic cycle

,

where water from oceans, lakes, soil, rivers, and veg-

etation evaporates, condenses, and then precipitates on

landmasses. The precipitation infi ltrates and recharges

groundwater or runs off into lakes, rivers, and oceans

(Fig. 13.10). Physical geographer Jamie Linton questions

the utility of any model of the water cycle that does not

take into account the role of humans and culture, sug-

gesting that by “representing water as a constant, cycli-

cal fl ow, the hydrologic cycle establishes a norm that is at

odds with the hydrological reality of much of the world”

(Linton 2008, 639).

Linton argues that the hydrologic cycle does not

take into account the norms of water in arid regions of the

world, and it also assumes water cycles in a predictable, lin-

ear fashion. The amount of water cycling through is not

a constant. For instance, landcover changes how much

water is in the cycle. In the global south, Linton, contends,

forests “can actually promote

Mountain and Sierra Nevada snows feed the Colorado

River and the aquifers that irrigate the California Central

Valley. Aqueducts snake their way across the desert to

urban communities. None of this has slowed the popu-

lation's move to the Sun Belt (see Chapter 12), and the

water situation there is becoming problematic. In coastal

eastern Spain, low water pressure in city pipes sometimes

deprive the upper fl oors of high-rise buildings of water.

In Southwest Asia and the Arabian Peninsula, grow-

ing populations strain ancient water supply systems and

desalinization plants are a necessity. Water plays a role in

regional confl icts in places including the Darfur region

of Sudan.

When relations between countries and peoples are

problematic, disputes over water can make them even

worse. As populations grow and as demand for water rises,

fears of future shortages intensify.

evapotranspiration at rates

much higher than for short crops,” which has “the overall

effect of

reducing

the quantity of water available for runoff

or groundwater recharge” (Linton 2008, 643).

Instead of the hydrologic cycle, Linton advocates

thinking of water as a system rather than a cycle (Fig. 13.11).

He defi nes the water system as the “integration of physi-

cal, biological, biogeochemical, and human components”

of the global water system.

Water and Politics in the Middle East

Water supply is a particularly diffi cult problem affecting

relations among Israel and its neighbors. With 7.7 mil-

lion people, Israel annually consumes nearly three times

as much water as Jordan, the West Bank Palestinian areas,

and Gaza combined (total population: over 7 million). As

much as half of Israel's water comes from sources outside

the Israeli state.

The key sources of water for the entire area are

the Jordan River and an aquifer beneath the West Bank.

When Israel captured the Golan Heights from Syria and

the West Bank from Jordan during the 1967 war, it gained

control over both of these sources, including the Jordan

Water Security

Throughout the world, people have come to depend on

water sources whose future capacity is uncertain. Rocky