Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

Arctic

Circl

e

6

0°

60°

ATLANTIC

PACIFIC

40°

40°

40°

40°

ATLANTIC

OCEAN

OCEAN

OCEAN

PACIFIC

20°

Tropic of Cancer

20°

20°

Tropic of Cancer

20°

OCEAN

INDIAN

OCEAN

0°

Equator

Equator

0°

ATLANTIC

20°

20°

20°

20°

20°

20°

20°

20°

Tropic of

Capricorn

Tropic of Capricorn

OCEAN

40°

40°

40°

40°

40°

40°

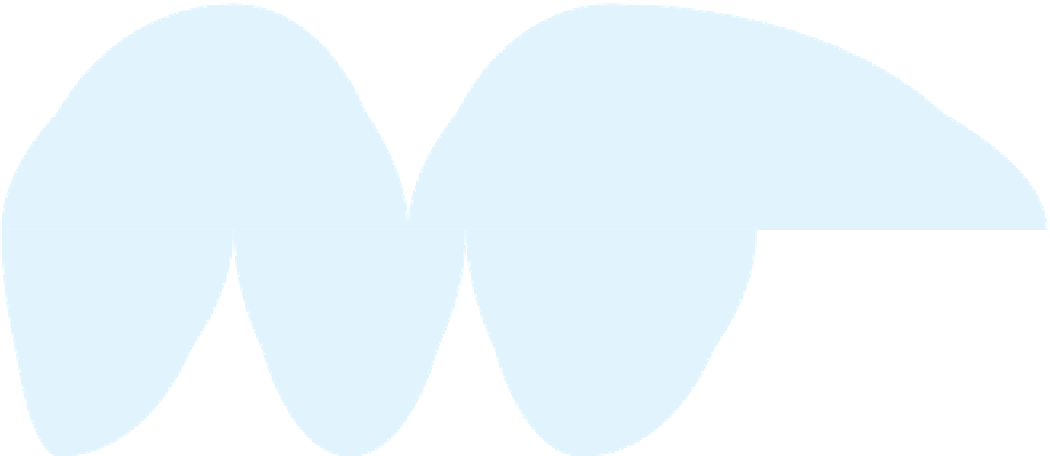

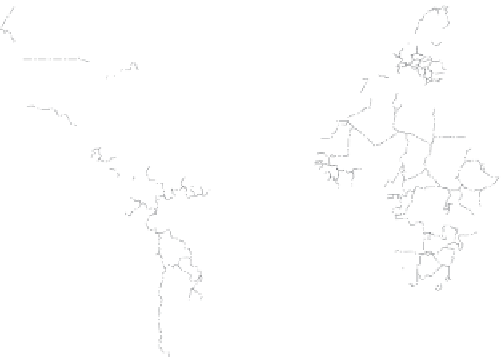

WORLD REGIONS OF PRIMARY

SUBSISTENCE AGRICULTURE

In the shaded areas, subsistence crop farming

is the l

eading way of

life. In an average year,

little surplus can be sold on markets.

160°

140°

120°

80°

60°

40°

0°

20°

40°

60°

100°

120°

140°

160°

60°

60°

60°

60°

60°

60°

60°

60°

Antarctic Circle

Figure 11.9

World Regions of Primarily Subsistence Agriculture.

Defi nitions of subsistence farming

vary. On this map, India and China are not shaded because farmers sell some produce at markets;

in Equatorial Africa and South America, subsistence farming allows little excess, and thus little

produce is sold at markets.

© E. H. Fouberg, A. B. Murphy, H. J. de Blij, and John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

change their livelihoods. In many cases, the state places

pressures on hunter-gatherers to settle in one place and

farm. Cyclical migration by hunter-gatherers does not

mesh well with bounded, territorial states. Some nongov-

ernmental organizations encourage settlement by digging

wells or building medical buildings, permanent houses, or

schools for hunter-gatherers. Even hunter-gatherers who

continue to use their knowledge of seeds, roots, fruits,

berries, insects, and animals to gather and trap the goods

they need for survival do so in the context of the world-

economy.

Unlike hunting and gathering, subsistence farming

continues to be a relatively common practice in Africa,

Middle America, tropical South America, and parts of

Southeast Asia (Fig. 11.9). The system of cultivation has

changed little over thousands of years. The term

subsis-

tence

can be used in the strictest sense of the word—that is,

to refer to farmers who grow food only to sustain them-

selves and their families, and fi nd building materials and

fi rewood in the natural environment, and who do not

enter into the cash economy at all. This defi nition fi ts

farmers in remote areas of South and Middle America,

Africa, and South and Southeast Asia. Yet many farm fam-

ilies living at the subsistence level sometimes sell a small

quantity of produce (perhaps to pay taxes). They are not

subsistence farmers in the strict sense, but the term

subsis-

tence

is surely applicable to societies where farmers with

small plots periodically sell a few pounds of grain on the

market but where poverty, indebtedness, and tenancy are

ways of life. For the indigenous peoples of the Amazon

Basin, the sedentary farmers of Africa's savanna areas, vil-

lagers in much of India, and peasants in Indonesia, subsis-

tence is not only a way of life but a state of mind.

Experience has taught farmers and their families that sub-

sistence farming is often precarious and that times of

comparative plenty will be followed by times of scarcity.

Subsistence farming has been in retreat for centu-

ries. From 1500 to 1950, European powers sought to

“modernize” the economies of their colonies by ending

subsistence farming and integrating farmers into colonial

systems of production and exchange. Sometimes their

methods were harsh: by demanding that farmers pay some

taxes, they forced subsistence farmers to begin selling

some of their produce to raise the necessary cash. They

also compelled many subsistence farmers to devote some

land to a crop to be sold on the world market such as cot-

ton, thus bringing them into the commercial economy.

The colonial powers encouraged commercial farming by

conducting soil surveys, building irrigation systems, and

establishing lending agencies that provided loans to farm-

ers. The colonial powers sought to make profi ts, yet it was

diffi cult to squeeze very much from subsistence-farming

areas. Forced cropping schemes were designed to solve

this problem. If farmers in a subsistence area cultivated a

certain acreage of, say, corn, they were required to grow a

specifi ed acreage of a cash crop as well. Whether this crop

would be grown on old land that was formerly used for

grain or on newly cleared land was the farmers' decision.

If no new lands were available, the farmers would have to

give up food crops for the compulsory cash crops. In many