Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

have high dependency ratios and also very high per cap-

ita GNIs. We can employ countless other statistics to

measure social welfare, including literacy rates, infant

mortality, life expectancy, caloric intake per person,

percentage of family income spent on food, and amount

of savings per capita.

Looking through all of the maps that measure devel-

opment, we gain a sense that many countries come out in

approximately the same position no matter which of these

measures is used. Each map and each statistic shares one

limit with per capita GNI: they do not capture differences

in development

within

countries, a question we consider

at the end of this chapter.

1,000

466

500

182

195

8

0

972

1,000

500

441

341

Development Models

This discussion of ways of measuring development takes

us back to another problem with terminology. The word

developing

suggests that all countries are improving their

place in each of these indicators, increasing literacy,

improving communications, or increasing productiv-

ity per worker. Beyond the problem of terminology, the

very effort to classify countries in terms of levels of devel-

opment has come under increasing attack. The central

concern is that development suggests a single trajectory

through which all countries move. The development

model, then, does not take geographical differences very

seriously. Just because Japan moved from a rural, agrarian

state to an urbanized, industrial one does not mean that

Mali will, or that it will do so in the same way. Another

criticism of the development model is that the conceptu-

alization of development has a Western bias. Critics argue

that some of the measures taken in poorer countries that

the West views as progress, such as attracting industry

and mechanizing agriculture, can lead to worsened social

and environmental conditions for many people in the

poorer countries. Still others criticize the development

model because it does not consider the ability of some

countries to infl uence what happens in other countries,

or the different positions countries occupy in the world

economy. Instead, the development model treats coun-

tries as autonomous units moving through a process of

development at different speeds.

The classic development model, one that is subject

to each of these criticisms, is economist Walt Rostow's

modernization model

. Many theories of development

grew out of the major decolonization movements of the

1960s. Concerned with how the dozens of newly indepen-

dent countries in Africa and Asia would survive economi-

cally, Rostow looked to how the economically powerful

countries had gotten where they were.

Rostow's model assumes that all countries fol-

low a similar path to development or modernization,

advancing through fi ve stages of development. In the

33

0

1,000

740

500

169

150

4

0

The

Netherlands

Mexico

Malawi

World

Average

Country

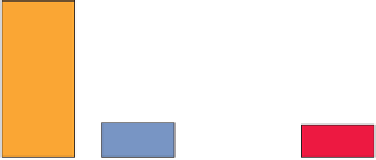

Figure 10.3

Differences in Communications Connectivity, 2005.

Data

from:

Earthtrends, World Resources Institute.

examined by summing production over the course of a

year and dividing it by the total number of persons in

the labor force. A more productive workforce points to

a higher level of mechanization in production. To mea-

sure access to technology, some analysts use transpor-

tation and communications facilities per person, which

reduces railway, road, airline connections, telephone,

radio, television, and so forth to a per capita index and

refl ects the amount of infrastructure that exists to facili-

tate economic activity. Figure 10.3 highlights some of

the extraordinary disparities in communications access

around the world.

Other analysts focus on social welfare to measure

development. One way to measure social welfare is the

dependency ratio

, a measure of the number of depen-

dents, young and old, that each 100 employed people

must support (Fig. 10.4). A high dependency ratio can

result in signifi cant economic and social strain. Yet, as

we saw in Chapter 2, the aging countries of Europe