Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

Cities in poorer parts of the world generally lack

enforceable

zoning laws.

Without zoning laws, cities in

the periphery have mixed land use throughout the city. For

example, in cities such as Madras, India (and in other cities

in India), open space between high-rise buildings is often

occupied by squatter settlements (Fig. 9.31). In Bangkok,

Thailand, elementary schools and noisy, polluting facto-

ries stand side by side. In Nairobi, Kenya, hillside villas

overlook some of Africa's worst slums. Over time, such

incongruities may disappear, as is happening in many cit-

ies in East Asia. Rising land values and greater demand for

enforced zoning regulations are transforming the central

cities of East Asia. But in South Asia, Subsaharan Africa,

Southwest Asia, North Africa, and Middle and South

America, unregulated, helter-skelter growth continues.

Across the global periphery, the one trait all major

cities display is the stark contrast between the wealthy and

poor. Sharp contrasts between wealthy and poor areas can

be found in major cities all over the world—for example,

homeless people sleeping on heating grates half a block

from the White House in Washington, D.C. Yet the inten-

sity and scale of the contrast are greater in cities of the

periphery. If you stand in the ce

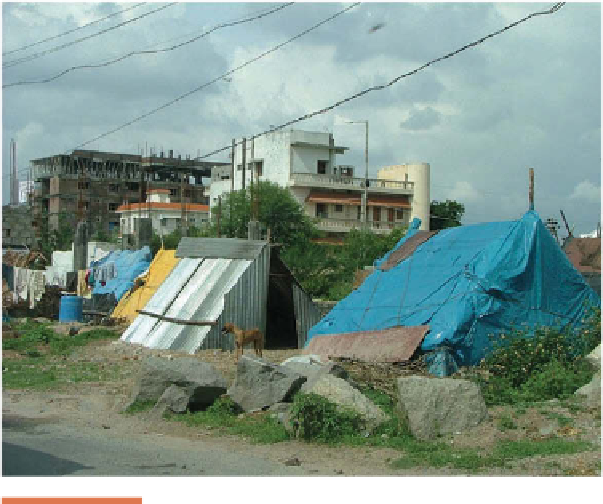

Figure 9.31

Hyderabad, India.

Temporary shelters, built to withstand the

summer monsoon, protect the migrants who work to build the

new construction in the background.

ntral area of Cairo, Egypt,

you see what appears to be a modern, Mediterranean

metropolis (Fig. 9.32). But if you get on a bus and ride it

toward the city's outskirts, that impression fades almost

immediately as paved streets give way to dusty alleys,

apartment buildings to harsh tenements, and sidewalk cof-

fee shops to broken doors and windows (Fig. 9.33). Traffi c-

choked, garbage-strewn, polluted Cairo is home to an esti-

mated 12.5 million people, more than one-fi fth of Egypt's

population; the city is bursting at the seams. And still

people continue to arrive, seeking the better life that pulls

countless m

© Erin H. Fouberg.

neighborhoods became increasingly rundown because

funds were not available for upkeep or to purchase homes

for sale.

Before the civil rights movement, realtors could pur-

posefully sell a house in a white neighborhood at a very low

price to a black buyer. In a practice called

blockbusting,

realtors would solicit white residents of the neighborhood

to sell their homes under the guise that the neighborhood

was going downhill because a black person or family

had moved in. This produced what urban geographers

and sociologists call

white fl ight

—movement of whites

from the city and adjacent neighborhoods to the outly-

ing suburbs. Blockbusting led to signifi cant turnover

in housing, which of course benefi ted real estate agents

through the commissions they earned as representatives

of buyers and sellers. Blockbusting also prompted land-

owners to sell their properties at low prices to get out of

the neighborhood quickly, which in turn allowed devel-

opers to subdivide lots and build tenements. Typically,

developers did not maintain tenements well, dropping the

property values even further.

Developers and governments are also important

actors in shaping cities. In cities of the global core that

have experienced high levels of suburbanization, people

have left the central business district for the suburbs for

a number of reasons, among them single-family homes,

yards, better schools, and safety. With suburbanization,

city governments lose tax revenue, as middle- and upper-

class taxpayers leave the city and pay taxes in the suburbs

instead. In order to counter the suburbanization trend,

igrants from the countryside year after year.

Shaping Cities in the Global Core

The goals people have in making cities have changed

over time. One way people make cities is by remaking

them, reinventing neighborhoods, or changing layouts to

refl ect current goals and aesthetics. During the segrega-

tion era in the United States, realtors, fi nancial lenders,

and city governments defi ned and segregated spaces in

urban environments. For example, before the civil rights

movement of the 1960s, fi nancial institutions in the busi-

ness of lending money could engage in a practice known

as

redlining

. They would identify what they considered

to be risky neighborhoods in cities—often predominately

black neighborhoods—and refuse to offer loans to anyone

purchasing a house in the neighborhood encircled by red

lines on their maps. This practice, which is now illegal,

worked against those living in poorer neighborhoods and

helped to precipitate a downward spiral in which poor