Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

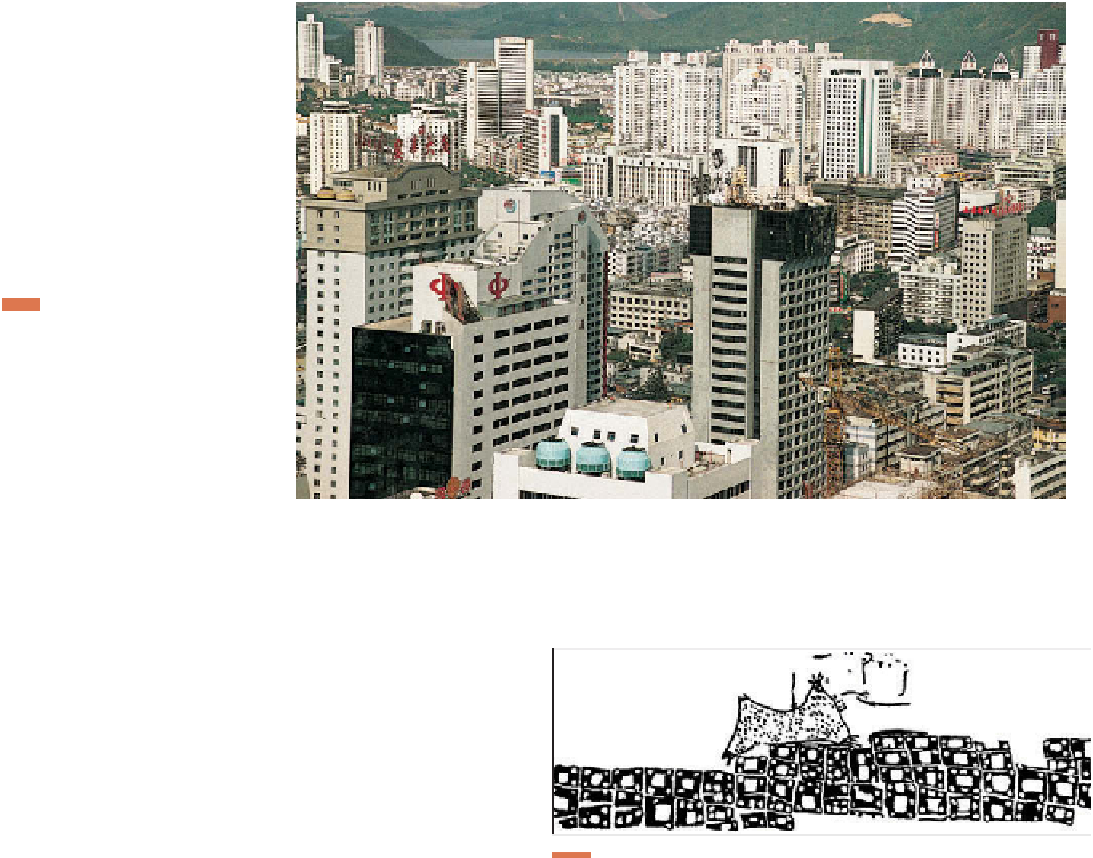

Figure 9.4

Shenzhen, China.

Shenzhen

changed from a fi shing village to a

major metropolitan area in just 25

years. Everything you see in this

photograph is less than 25 years

old; all of this stands where duck

ponds and paddies lay less than

three decades ago.

© H. J. de Blij.

Some cities grew out of agricultural villages, and

others grew in places previously unoccupied by sed-

entary people. The innovation of the city is called the

fi rst

urban revolution

, and it occurred independently

in six separate hearths, a case of independent inven-

tion

1

(Fig. 9.6). In each of the urban hearths, people

became engaged in economic activities beyond agricul-

ture, including specialty crafts, the military, trade, and

government.

The six urban hearths are tied closely to the hearths

of agriculture. The fi rst hearth of agriculture, the Fertile

Crescent, is the fi rst place archaeologists fi nd evidence

of cities, dating to about 3500

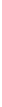

Figure 9.5

Catal Huyuk.

Dated to 12,000 years ago, the early city of

Catal Huyuk was in a western extension of the Fertile Crescent,

in present-day Turkey. This image is a reproduction of cave art

found in Catal Huyuk. Archaeologists interpreted the cone struc-

ture in the background as a volcano, and the square sin the front

as houses. Adapted from James Mellaart,

Catal Huyuk: A Neolithic

Town in Anatolia,

1967, McGraw-Hill.

. This urban hearth is

called

Mesopotamia

, referring to the region of great cit-

ies (such as Ur and Babylon) located between the Tigris

and Euphrates rivers. Studies of the cultural landscape

and urban morphology of Mesopotamian cities have

found signs of social inequality in the varying sizes and

ornamentation of houses. Urban elite erected palaces,

protected themselves with walls, and employed countless

artisans to beautify their spaces. They also established a

priest-king class and developed a religious-political ide-

ology to support the priest-kings. Rulers in the cities

were both priests and kings, and they levied taxes and

demanded tribute from the harvest brought by the agri-

cultural laborers.

bce

Archaeologists, often teaming up with anthro-

pologists and geographers, have learned much about the

ways ancient Mesopotamian cities functioned by study-

ing the urban morphology of the cities. The ancient

Mesopotamian city was usually protected by a mud wall

surrounding the entire community, or sometimes a cluster

of temples and shrines at its center. Temples dominated

the urban landscape, not only because they were the larg-

est structures in town but also because they were built on

artifi cial mounds often over 100 feet (30 meters) high.

In Mesopotamia, priests and other authorities

resided in substantial buildings, many of which might

1

Some scholars argue that there are fewer than fi ve hearths and attribute

more urbanization to diffusion.