Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

response to issues in the future. Small wonder, then, that

many individuals who have little general understanding of

geography at least appreciate the impo

Many borders were established on the world map

before the extent or signifi cance of subsoil resources was

known. As a result, coal seams and aquifers cross boundar-

ies, and oil and gas reserves are split between states. Europe's

coal reserves, for example, extend from Belgium underneath

the Netherlands and on into the Ruhr area of Germany.

Soon after mining began in the mid-nineteenth century,

these three neighbors began to accuse each other of mining

coal that did not lie directly below their own national ter-

ritories. The underground surveys available at the time were

too inaccurate to pinpoint the ownership of each coal seam.

During the 1950s-1960s, Germany and the Neth-

erlands argued over a gas reserve that lies in the subsoil

across their boundary. The Germans claimed that the

Dutch were withdrawing so much natural gas that the gas

was fl owing from beneath German land to the Dutch side

of the boundary. The Germans wanted compensation for

the gas they felt they lost. A major issue between Iraq and

Kuwait, which in part led to Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in

1990, was the oil in the Rumaylah reserve that lies under-

neath the desert and crosses the border between the two

states. The Iraqis asserted that the Kuwaitis were drilling

too many wells and draining the reserve too quickly; they

also alleged that the Kuwaitis were drilling oblique bore-

holes to penetrate the vertical plane extending downward

along the boundary. At the time the Iraq-Kuwait bound-

ary was established, however, no one knew that this giant

oil reserve lay in the subsoil or that it would contribute to

an international crisis (Fig. 8.19).

Above the ground, too, the interpretation of bound-

aries as vertical planes has serious implications. A state's

“airspace” is defi ned by the atmosphere above its land

area as marked by its boundaries, as well as by what lies

beyond, at higher altitudes. But how high does the airspace

rtance of its elec-

toral geography component.

Choose an example of a devolutionary movement and

consider which geographic factors favor, or work against,

greater autonomy (self-governance) for the region. Would

granting the region autonomy strengthen or weaken the

state in which the region is currently situated?

HOW ARE BOUNDARIES ESTABLISHED, AND

WHY DO BOUNDARY DISPUTES OCCUR?

The territories of individual states are separated by

international boundaries, often referred to as borders.

Boundaries may appear on maps as straight lines or may

twist and turn to conform to the bends of rivers and the

curves of hills and valleys. But a boundary is more than

a line, far more than a fence or wall on the ground. A

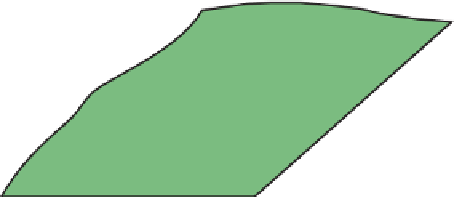

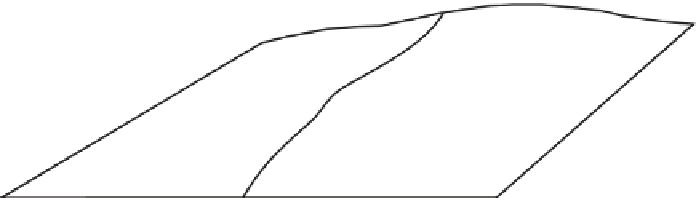

boundary

between states is actually a vertical plane that

cuts through the rocks below (called the subsoil) and the

airspace above, dividing one state from another (Fig.

8.18). Only where the vertical plane intersects the Earth's

surface (on land or at sea) does it form the line we see on

the ground.

Figure 8.18

The Vertical Plane of a Political

Boundary.

© E. H. Fouberg, A. B. Murphy,

H. J. de Blij, and John Wiley & Sons, Inc.