Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

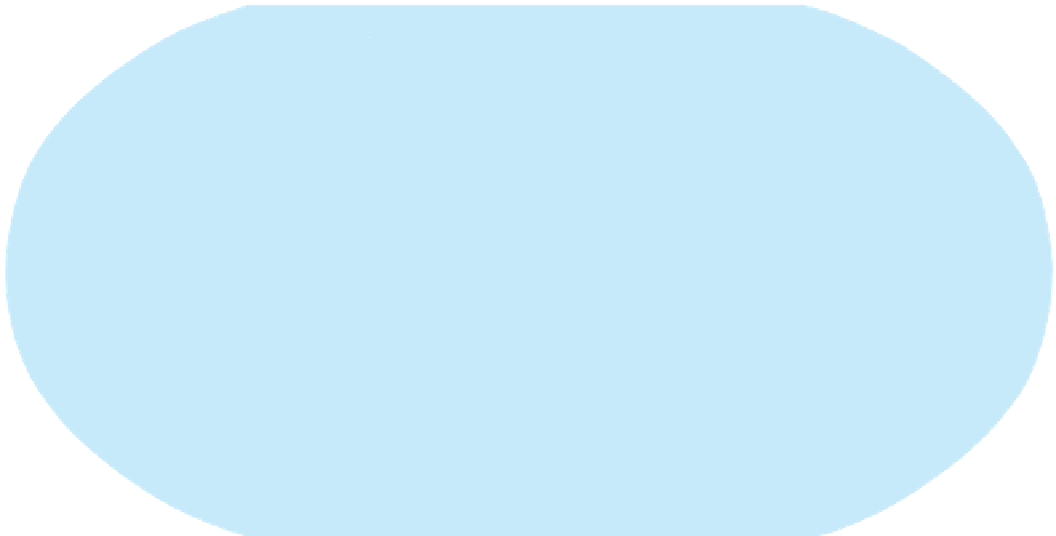

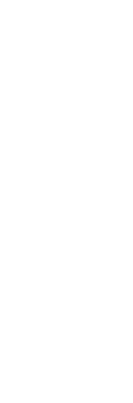

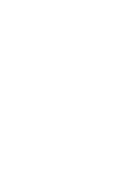

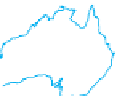

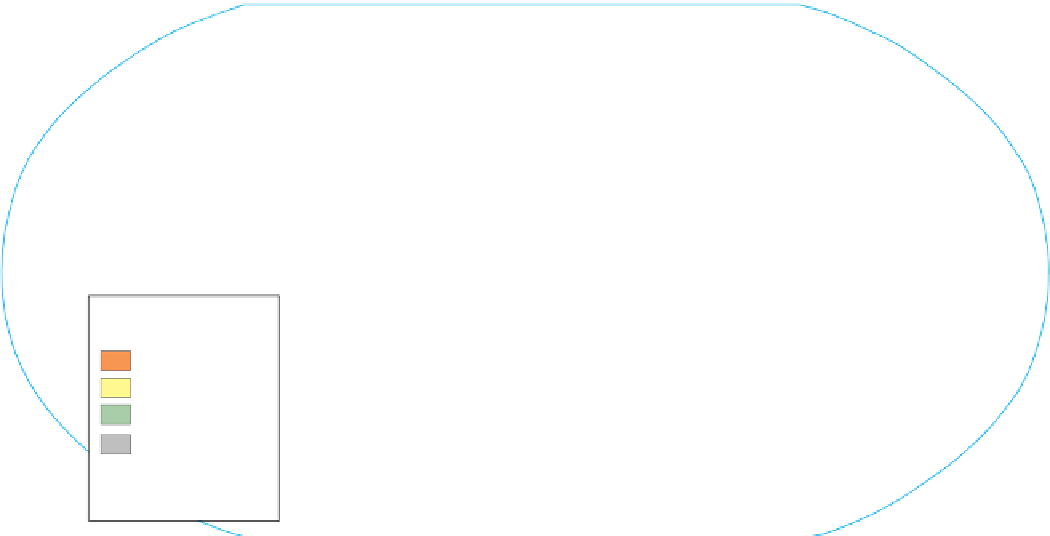

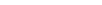

Figure 8.10

The World Economy.

One representation of core, periphery, and semi-periphery based on

a calculation called World-Economy Centrality, derived by sociologist Paul Prew. The authors

took into consideration factors not quantifi ed in Prew's data, including membership in the

European Union, in moving some countries from the categories Prew's data recommended to

other categories.

Data from: Paul Prew, World-Economy Centrality and Carbon Dioxide Emissions: A New Look at the

Position in the Capitalist World-System and Environmental Pollution, American Sociological Association, 12, 2 (2010) 162-191.

ARCTIC OCEAN

PACIFIC

OCEAN

ATLANTIC

OCEAN

PACIFIC

OCEAN

INDIAN

OCEAN

THE WORLD-

ECONOMY

Core

Semi-periphery

Periphery

Disputed depending

on criteria used

0

2000 Miles

0

2000 Kilometers

Figure 8.10 presents one way of dividing up the

world in world-systems terms. The map designates some

states as part of the

semiperiphery

—places where core

and periphery processes are both occurring—places that

are exploited by the core but in turn exploit the periphery.

The semiperiphery acts as a buffer between the core and

periphery, preventing the polarization of the world into

two extremes.

Political geographers, economic geographers, and

other academics continue to debate world-systems theory.

The major concerns are that it overemphasizes economic

factors in political development, that it is very state-centric,

and that it does not fully account for how places move

from one category to another. Nonetheless, Wallerstein's

work has encouraged many to see the world political map

as a system of interlinking parts that need to be under-

stood in relation to one another and as a whole. As such,

the impact of world-systems theory has been considerable

in political geography, and it is increasingly commonplace

for geographers to refer to the kinds of core-periphery

distinctions suggested by world-systems theory.

World-systems theory helps explain how colonial

powers were able to amass great concentrations of wealth.

During the fi rst wave of colonialism, colonizers extracted

goods from the Americas and the Caribbean and exploited

Africa for slave labor, amassing wealth through sugar, cof-

fee, fruit, and cotton production. During the second wave

of colonialism, which happened after the Industrial Revo-

lution, colonizers set their sights on cheap industrial labor,

cheap raw materials, and large-scale agricultural plantations.

Not all core countries in the world today were colo-

nial powers, however. Countries including Switzerland,

Singapore, and Australia have signifi cant global clout

even though they were never classic colonial powers, and

that clout is tied in signifi cant part to their positions in the

global economy. The countries gained positions through

access to the networks of production, consumption, and

exchange in the wealthiest parts of the world and through

their ability to take advantage of that access.

World-Systems and Political Power

Are economic power and political power one and the

same? No, but certainly economic power can bring politi-

cal power. In the current system, economic power means

wealth, and political power means the ability to infl uence

others to achieve your goals. Political power is not simply

a function of sovereignty. Each state is theoretically sover-

eign, but not all states have the same

ability

to infl uence

others or achieve their political goals. Having wealth helps

leaders amass political power. For instance, a wealthy