Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

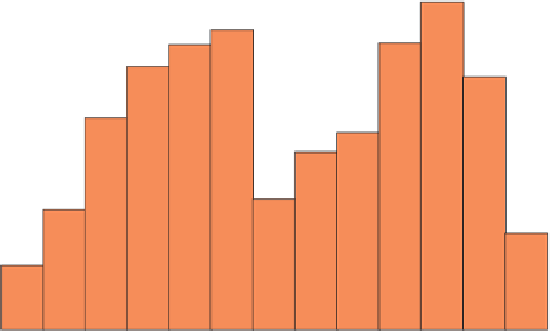

Figure 8.7

Two Waves of Colonialism between

1500 and 1975.

Each bar shows the total

number of colonies around the world.

Adapted with permission from:

Peter J. Taylor and Colin

Flint,

Political Geography: World-Economy, Nation-State

and Locality,

4th ed., New York: Prentice Hall, 2000.

sixteenth century, Spain and Portugal took advantage of

an increasingly well-consolidated internal political order

and newfound wealth to expand their infl uence to increas-

ingly far-fl ung realms during the fi rst wave of colonial-

ism. Later joined by Britain, France, the Netherlands, and

Belgium, the fi rst wave of colonialism established a far-

reaching political and economic system. After indepen-

dence movements in the Americas during the late 1700s

and 1800s, a second wave of colonialism began in the late

1800s. The major colonizers were Britain, France, the

Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and Italy. The coloniz-

ing parties met for the Berlin Conference in 1884-1885

and arbitrarily laid out the colonial map of Africa with-

out reference to indigenous cultural or political arrange-

ments. Driven by motives ranging from economic profi t

to the desire to bring Christianity to the rest of the world,

colonialism projected European power and a European

approach to organizing political space into the non-Euro-

pean world (Fig. 8.8).

With Europe in control of so much of the world,

Europeans laid the ground rules for the emerging inter-

national state system, and the modern European concept

of the nation-state became the model adopted around the

world. Europe also established and defi ned the ground

rules of the capitalist world economy, creating a system of

economic interdependence that persists today.

During the heyday of

colonialism

, the imperial pow-

ers exercised ruthless control over their domains and

organized them for maximum economic exploitation. The

capacity to install the infrastructure necessary for such

effi cient profi teering is itself evidence of the power rela-

tionships involved: entire populations were regimented

in the service of the colonial ruler. Colonizers organized

the fl ows of raw materials for their own benefi t, and we

can still see the tangible evidence of that organization

(plantations, ports, mines, and railroads) on the cultural

landscape.

Despite the end of colonialism, the political organi-

zation of space and the global world economy persist. And

while the former colonies are now independent states,

their economies are anything but independent. In many

cases raw material fl ows are as great as they were before

the colonial era came to an end. For example, today in

Gabon, Africa, the railroad goes from the interior forest,

which is logged for plywood, to the major port and capi-

tal city, Libreville. The second largest city, Port Gentil,

is located to the south of Libreville, but the two cities are

not connected directly by road or railroad. As the crow

fl ies, the cities are 90 miles apart, but if you drive from one

to the other, the circuitous route will take you 435 miles.

Both cities are export focused. Port Gentil is tied to the

global oil economy, with global oil corporations respon-

sible for building much of the city and its housing, and

employing many of its people.

Construction of the Capitalist World Economy

The long-term impacts of colonialism are many and var-

ied. One of the most powerful impacts of colonialism

was the construction of a global order characterized by

great differences in economic and political power. The

European colonial enterprise gave birth to a globalized

economic order in which the European states and areas

dominated by European migrants emerged as the major

centers of economic and political activity. Through