Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

The goal of creating nation-states dates to the

French Revolution, which sought to replace control by a

monarchy or colonizer with an imagined cultural-historical

community of French people. The Revolution initially

promoted

democracy

, the idea that the people are the

ultimate sovereign—that is, the people, the

nation

, have

the ultimate say over what happens within the state. Each

nation, it was argued, should have its own sovereign terri-

tory, and only when that was achieved would true democ-

racy and stability exist.

People began to see the idea of the nation-state as

the ultimate form of political-territorial organization,

the right expression of sovereignty, and the best route to

stability. The key problem associated with the idea of the

nation-state is that it assumes the presence of reasonably

well-defi ned, stable nations living contiguously within

discrete territories. Very few places in the world come

close to satisfying this requirement. Nonetheless, in the

Europe of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many

believed the assumption could be met.

The quest to form nation-states in the Europe of the

1800s was associated with a rise in nationalism. We can view

nationalism from two vantage points: that of the people and

that of the state. When

people

have a strong sense of nation-

alism, they have a loyalty to and a belief in the nation itself.

This loyalty does not necessarily coincide with the borders

of the state. A

state

, in contrast, seeks to promote a sense of

nationhood that coincides with its own borders. In the name

of nationalism, a state with more than one nation within its

borders may attempt to build a single national identity out

of the divergent people within its borders. In the name of

nationalism, a state may also promote confl ict with another

state that it sees as threatening to its territorial integrity.

Even though the roots of nationalism lie in ear-

lier centuries, the nineteenth century was the true age

of nationalism in Europe. In some cases the pursuit of

nationalist ambitions produced greater cohesion within

long-established states, such as in France or Spain; in

other cases nationalism became a rallying cry for bring-

ing together people with some shared historical or cul-

tural elements into a single state, such as in the cases of

Italy or Germany. Similarly, people who saw themselves as

separate nations within other states or empires launched

successful separatist movements. Ireland, Norway, and

Poland all serve as examples of this phenomenon.

European state leaders used the tool of nationalism

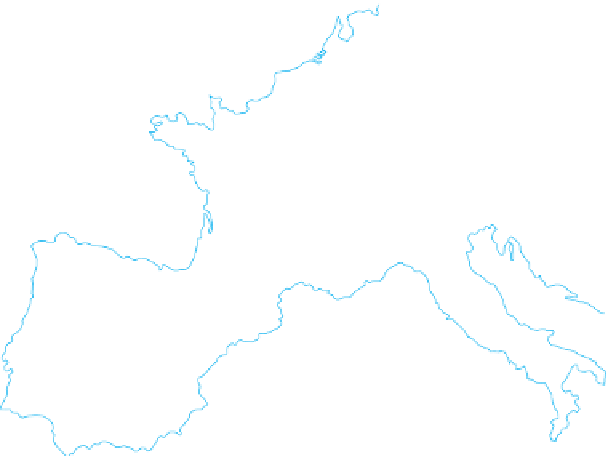

to strengthen the state. The modern map of Europe is still

fragmented, but much less so than in the 1600s (Fig. 8.4).

In the process of creating nation-states in Europe, states

absorbed smaller entities into their borders, resolved

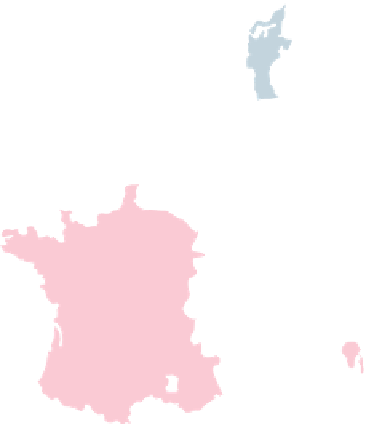

Figure 8.4

European Political Fragmentation in 1648.

A generalized map of the fragmentation of

western Europe in the 1600s.

Adapted with permission from:

Geoffrey Barraclough, ed.

The Times Concise Atlas of

World History,

5th ed., Hammond Incorporated, 1998.