Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

Guest

Field Note

Ardmore, Ireland

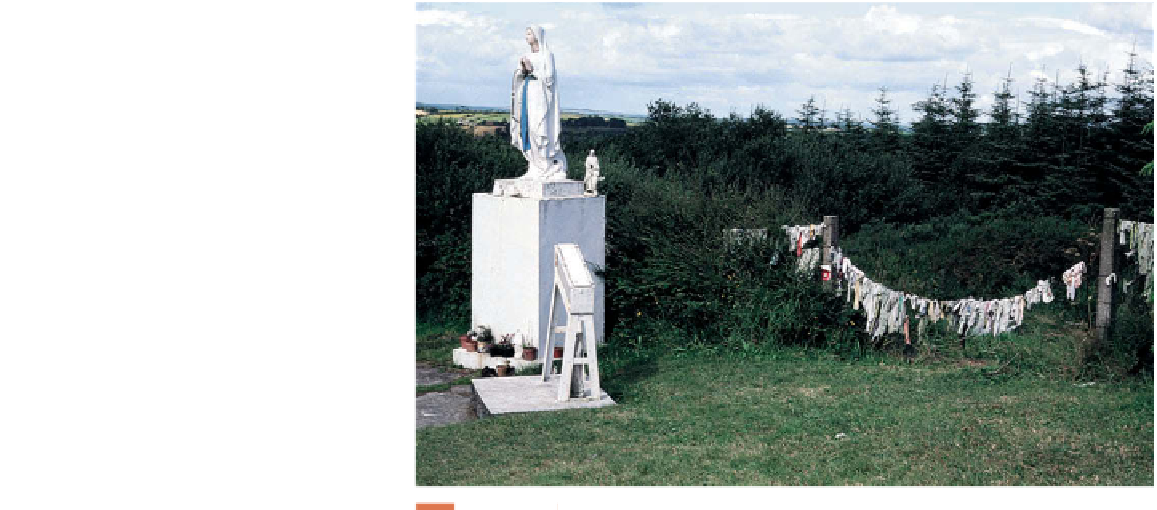

At St. Declan's Holy Well in Ireland, I found a

barbed wire fence substituting for the more

traditional thorn tree as a place to hang

scraps of clothing as offerings. This tradition,

which died out long ago in most parts of Con-

tinental Europe, was one of many aspects of

Irish pilgrimage that led me to speculate on

“Galway-to-the-Ganges” survival of very old

religious customs on the extreme margins of

an ancient Indo-European culture realm. My

subsequent fi eldwork focused on contem-

porary European pilgrimage, but my curios-

ity about the geographical extent of certain

ancient pilgrimage themes lingered. While

traveling in Asia, I found many similarities

among sacred sites across religions. Each reli-

gion has formation stories, explanations of how particular sites, whether Buddhist monasteries or Irish wells, were recog-

nized as sacred. Many of these stories have similar elements. And, in 1998, I traveled across Russia from the remote Kam-

chatka Peninsula to St. Petersburg. Imagine my surprise to fi nd the tradition of hanging rag offerings on trees alive and well

all the way across the Russian Far East and Siberia, at least as far as Olkon Island in Lake Baikal.

Credit: Mary Lee Nolan, Oregon State University

Figure 7.19

diffused to Ireland, the Catholic Church usurped many

of these features, infusing them with Christian meaning.

Nolan described the marriage of Celtic sacred sites and

Christian meaning:

cerns, and the act of designating certain sacred spaces

as public recreational or tourist areas. Geographer

Kari Forbes-Boyte studied Bear Butte, a site sacred

to members of the Lakota and Cheyenne people in

the northern Great Plains of the United States and a

site that became a state park in the 1960s. Bear Butte

is used today by both Lakota and Cheyenne people in

religious ceremonies and by tourists who seek access

to the recreational site. Nearby Devils Tower, which

is a National Monument, experiences the same pull

between religious use by American Indians and recre-

ational use by tourists.

Places such as Bear Butte and Devils Tower experi-

ence contention when one group sees the sites as sacred

and another group does not. In many parts of the world,

sacred sites are claimed as holy or signifi cant to adher-

ents of more than one religious faith. In India several

sites are considered sacred by Hindus, Buddhists, and

Jains. Specifi cally, Volture Peak in Rajgir in northeast-

ern India is holy to Buddhists because it is the site where

Buddha fi rst proclaimed the Heart Sutra, a very impor-

tant canon of Buddhism. Hindus and Jains also consider

the site holy because they consider Buddha to be a god or

prophet. Fortunately, this site has created little discord

among religious groups. Pilgrims of all faiths peacefully

The early Celtic Church was a unique institution, more

open to syncretism of old and new religious traditions

than was the case in many other parts of Europe. Old holy

places, often in remote areas, were “baptized” in the new

religion or given new meaning through their historical,

or more often legendary, association with Celtic saints.

Such places were characterized by sacred site features

such as heights, insularity, or the presence of holy water

sources, trees, or stones.

Nolan contrasted Irish sacred sites with those in conti-

nental Europe, where sacred sites were typically built in

urban, accessible areas. In continental Europe, Nolan

found that the “sacred” (bones of saints or images) was

typically brought to a place in order to infuse the place

with meaning.

In many societies, features in the physical geo-

graphic landscape remain sacred to religious groups.

Access to and use of physical geographic features are

constrained by private ownership, environmental con-

225