Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

to speak the language of the colonizer. These language

policies continued in many places until recently and were

enforced primarily through public (government) and

church (mission) schools.

American, Canadian, Australian, Russian, and New

Zealand governments each had policies of forced assimila-

tion during the twentieth century, including not allowing

indigenous peoples to speak native languages. For example,

the United States forced American Indians to learn and speak

English. Both mission schools and government schools

enforced English-only policies in hopes of assimilating

American Indians into the dominant culture. In an interview

with the producers of an educational video, Clare Swan, an

elder in the Kenaitze band of the Dena'ina Indians in Alaska,

eloquently described the role of language in culture:

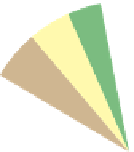

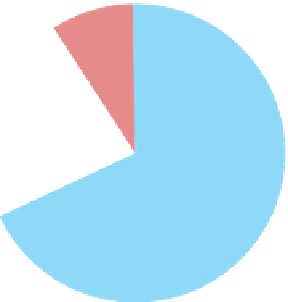

INTERNET CONTENT, BY LANGUAGE

Other

9%

Russian

2%

Spanish

2%

French

3%

Chinese

4%

German

6%

Japanese

6%

English

68%

INTERNET USERS, BY LANGUAGE SPOKEN

No one was allowed to speak the language—the Dena'ina

language. They [the American government] didn't allow

it in schools, and a lot of the women had married non-

native men, and the men said, “You're American now so

you can't speak the language.” So, we became invisible in

the community. Invisible to each other. And, then, because

we couldn't speak the language

—what happens when

you can't speak your own language is you have to

think with someone else's words, and that's a dread-

ful kind of isolation

[emphasis added].

Other

18%

English

27%

Korean

2%

Russian

3%

French

3%

Arabic

3%

German

4%

Portuguese

4%

Shared language makes people in a culture visible to each

other and to the rest of the world. Language helps to bind

a cultural identity. Language is also quite personal. Our

thoughts, expressions, and dreams are articulated in our

language; to lose that ability is to lose a lot.

Language can reveal much about the way people

and cultures view reality. Some African languages have no

word or term for the concept of a god. Some Asian lan-

guages have no tenses and no system for reporting chron-

ological events, refl ecting the lack of cultural distinction

between then and now. Given the American culture's pre-

occupation with dating and timing, it is diffi cult for many

in the United States to understand how speakers of these

languages perceive the world.

Language is so closely tied to culture that people use

language as a weapon in cultural confl ict and political strife.

In the United States, where the Spanish-speaking popula-

tion is growing (Fig. 6.5), some Spanish speakers and their

advocates are demanding the use of Spanish in public affairs.

In turn, people opposed to the use of Spanish in the United

States are leading countermovements to promote “Offi cial

English” policies, where English would be the offi cial lan-

guage of government. Of course, Spanish is one of many

non-English languages spoken in the United States, but it

overshadows all others in terms of number of speakers and

is therefore the focus of the offi cial English movement

(Table 6.1). During the 1980s, over 30 different States con-

sidered passing laws declaring English the State's offi cial

Chinese

23%

Japanese

5%

Spanish

8%

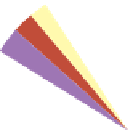

TOP 10 LANGUAGES, BY MILLIONS OF SPEAKERS

German

100

Japanese

125

Russian

167

Portuguese

176

Chinese

1,213

Bengali

207

Spanish

322

English

341

Arabic

422

Hindi

366

Figure 6.4

Languages used on the Internet.

Data from

: Internet World

Stats: Usage and Population Statistics. www.internetworldstats.

com/stats7.htm.