Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

Guest

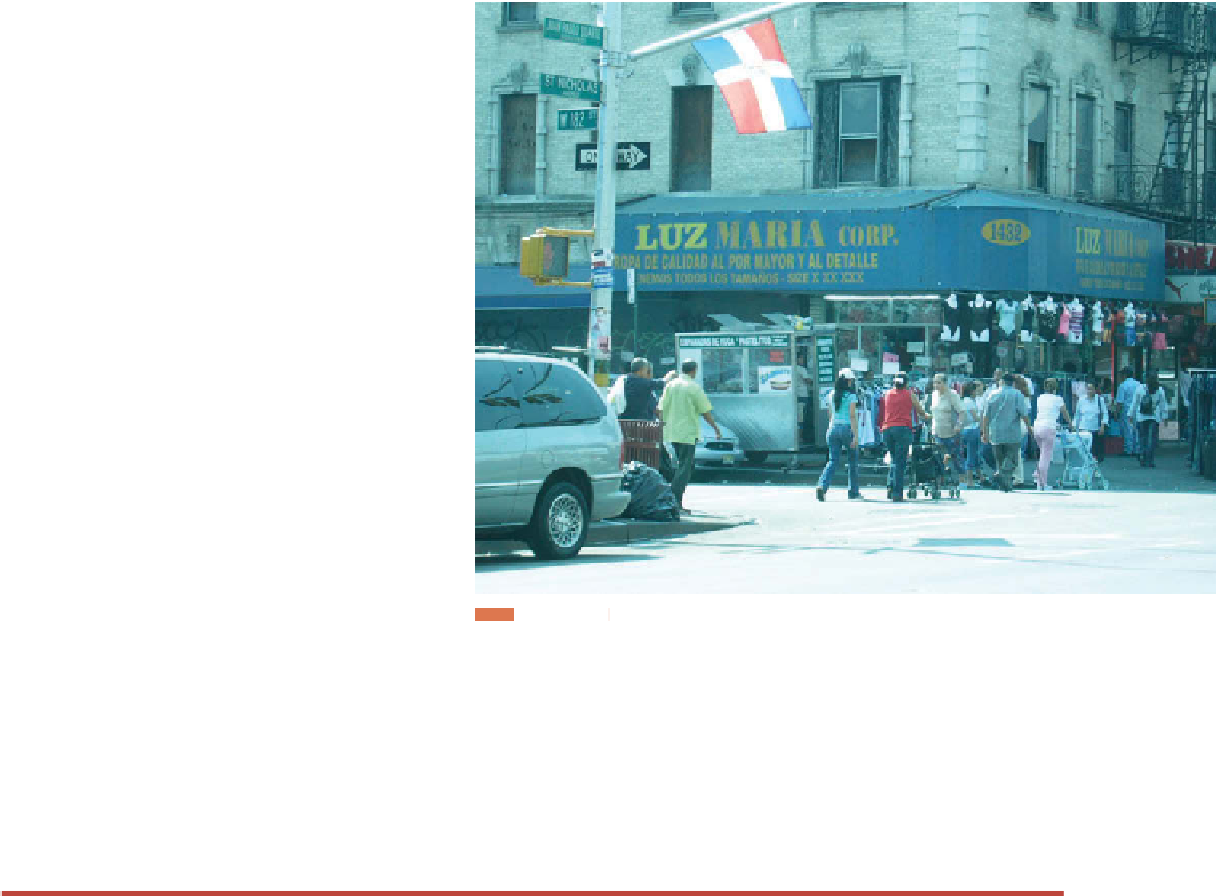

Field Note

Washington Heights, New York

It is a warm, humid September morning, and the

shops along Juan Pablo Duarte Boulevard are already

bustling with customers. The Dominican fl ag waves

proudly from each corner's traffi c signal. Calypso

and salsa music ring through the air, as do the

voices of Dominican grandmothers negotiating for

the best prices on fresh mangos and papayas. The

scents of fresh

empanadas de yuca

and

pastelitos

de pollo

waft from street vendor carts. The signage,

the music, the language of the street are all in Span-

ish and call out to this Dominican community. I am

not in Santo Domingo but in Washington Heights in

upper Manhattan in New York City.

Whenever I exit the “A” train at 181st Street and

walk toward St. Nicholas Avenue, renamed here Juan

Pablo Duarte Boulevard for the founding father of the

Dominican Republic, it is as if I have boarded a plane

to the island. Although there are Dominicans living

in most neighborhoods of New York's fi ve boroughs,

Washington Heights serves as the heart and soul of

the community. Dominicans began settling in Washington Heights in 1965, replacing previous Jewish, African American, and

Cuban residents through processes of invasion and succession. Over the past 40 years they have established a vibrant social

and economic enclave that is replenished daily by transnational connections to the residents' homeland. These transnational

links are pervasive on the landscape, and include travel agencies advertising daily fl ights to Santo Domingo and Puerto Plata

and stores handling

cargas, envios

, and

remesas

(material and fi nancial remittances) found on every block, as well as

farmacias

(pharmacies) selling traditional medicines and

botanicas

selling candles, statues, and other elements needed by practitioners

of Santería, a syncretistic blending of Catholicism and Yoruba beliefs practiced among many in the Spanish Caribbean.

Credit: Ines Miyares, Hunter College of the City University of New York.

Figure 5.7

norms. Miyares cautions, however, that not all Hispanics

in the city are categorically assimilated into the Caribbean

culture. Rather, the local identities of the Hispanic popu-

lations in New York vary by “borough, by neighborhood,

by era, and by source country and entry experience.” Since

1990, the greatest growth in the Hispanic population of

New York has been Mexican. Mexican migrants have set-

tled in a variety of ethnic neighborhoods, living alongside

new Chinese immigrants in Brooklyn and Puerto Ricans

in East Harlem. The process of succession continues in

New York, with Mexican immigrants moving into and

succeeding other Hispanic neighborhoods, sometimes

producing tensions between and among the local cultures.

In New York and in specifi c neighborhoods such as

East Harlem, the word

Hispanic

does little to explain the

diversity of the city. At these scales, different identities are

claimed and assigned, identities that refl ect local cultures

and neighborhoods. The overarching category “His-

panic” tells us even less about diversity when one moves

up to the scale of the United States, but as long as that

category persists in the Census, people will be encouraged

to think about it as a meaningful basis for understanding

social differences.

Recall the last time you were asked to check a box for

your race. Does that box factor into how you make sense

of yourself individually, locally, regionally, nationally, and

globally? What impact might it have on how other people

view you?

154