Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

Field Note

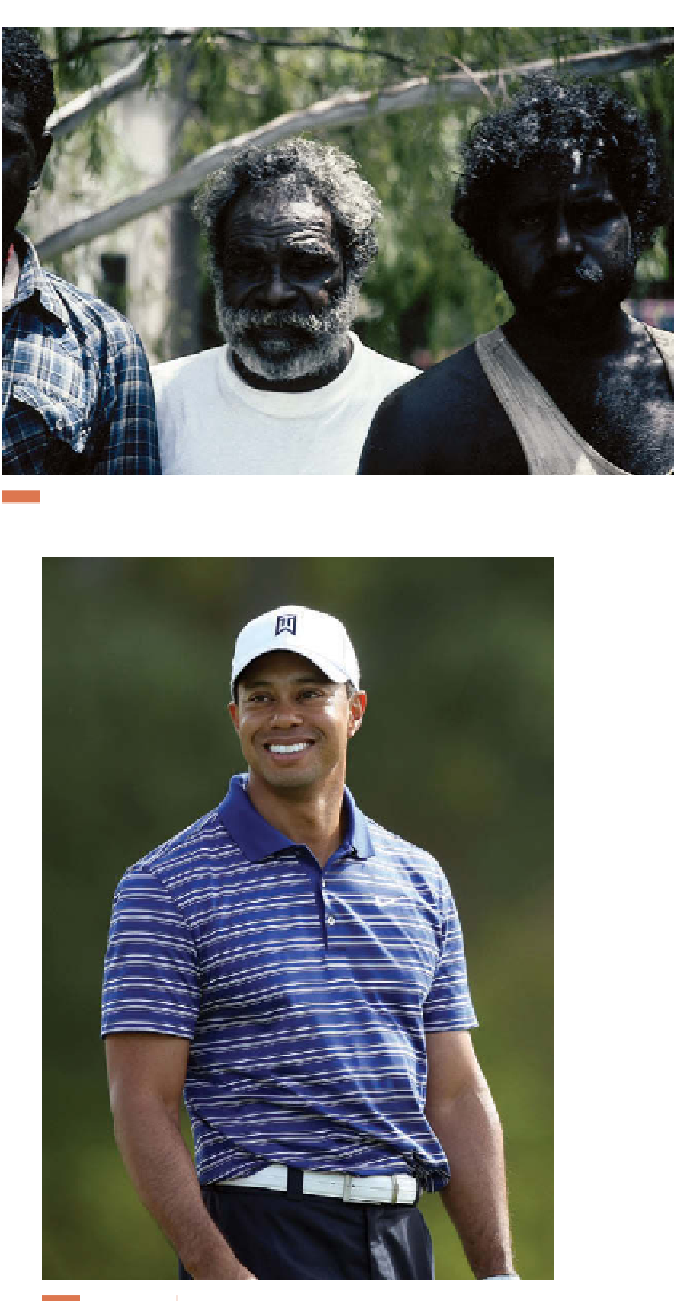

“We were traveling in Darwin, Australia, in 1994 and

decided to walk away from the modern downtown for

a few hours. Darwin is a multicultural city in the midst

of a region of Australia that is largely populated by

Aboriginals. At the bus stops on the outskirts of the

city, Aboriginals reached Darwin to work in the city or

to obtain social services only offered in the city. With a

language barrier between us, we used hand gestures to

ask the man in the white shirt and his son if we could take

their picture. Gesturing back to us, they agreed to the

picture. Our continued attempts at sign language soon

led to much laughter among the people waiting for the

next bus.”

Figure 5.3

Darwin, Australia.

© H. J. de Blij

of class placement, in which members of the wealthy upper

class are generally considered as “white,” members of the

middle class as mixed race or Mestizo, and members of the

lower class as “black.” Indeed, because racial classifi cations

are based on class standing and physical appearance rather

than ancestry, “the designation of one's racial identity need

not be the same as that of the parents, and siblings are often

classifi ed differently than one another.”

In each of these cases, and in countless others, peo-

ple have constructed racial categories to justify power,

economic exploitation, and cultural oppression.

Race and Ethnicity in the United States

Unlike a local culture or ethnicity to which we may

choose

to belong, race is an identity that is more often

assigned

.

In the words, once again, of Benjamin Forest: “In many

respects, racial identity is not a self-consciously con-

structed collection of characteristics, but a condition

which is imposed by a set of external social and histori-

cal constraints.” In the United States, racial categories

are reinforced through residential segregation, racialized

divisions of labor, and the categories of races recorded by

the United States Census Bureau and other government

and nongovernmental agencies.

Defi nitions of races in the United States histori-

cally focused on dividing the country into “white” and

“nonwhite,” but how these categories are understood has

changed over time (Figure 5.4). For example, when immi-

gration to the United States shifted from northern and

western Europe to southern and eastern Europe in the

early twentieth century, the United States government

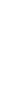

Figure 5.4

Tiger Woods.

When Tiger Woods emerged as a serious con-

tender in the golf circuit in the 1990s, the media was uncertain

in which race “box” he fi t. In response, Woods defi ned himself

as a Cablinasian for Caucasian, Black, American Indian, and

Asian.

© Donald Miralle/Getty Images.