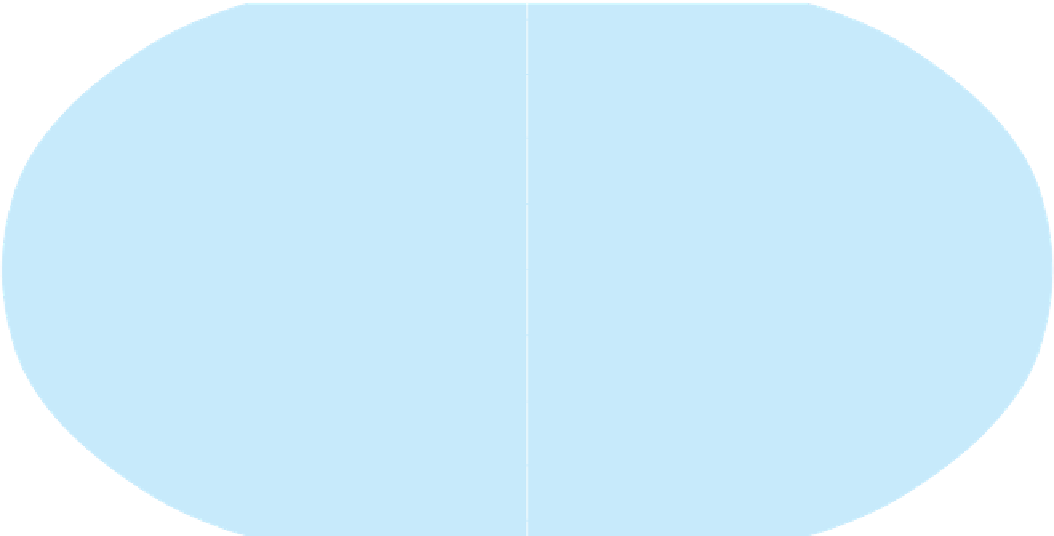

Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

Arctic Circle

RUSSIA

60

°

Moscow

CANADA

GER.

Toronto

N.

KOREA

Chicago

Beijing

New York

JAPAN

40

°

Seoul

TURKEY

UNITED STATES

Philadelphia

SPAIN

Incheon

CHINA

S. KOREA

Tokyo

Atlanta

Dallas

ATLANTIC

OCEAN

Wuhan

KUWAIT

Shanghai

ISRAEL

Houston

Dubai

Manama

Shenzhen

Guangzhou

Tropic of Cancer

TAIWAN

SAUDI

ARABIA

U.A.E.

20

°

Hong Kong

THAILAND

PACIFIC

OCEAN

PHILIPPINES

PACIFIC

OCEAN

MALAYSIA

Kuala Lumpur

0

Equator

Singapore

°

INDIAN

OCEAN

INDONESIA

NUMBER OF BUILDINGS

OVER 780 FEET TALL

10 or more

6-9

3-5

1-2

20

°

Tropic of Capricorn

AUSTRALIA

Sydney

Melbourne

40

°

0

2000

4000 Kilometers

0

1000

2000 Miles

160

°

140

°

120

°

100

°

80

°

60

°

40

°

20

°

0

°

40

°

60

°

80

°

100

°

120

°

140

°

20

°

160

°

60

°

Antarctic Circle

SOUTHERN

OCEAN

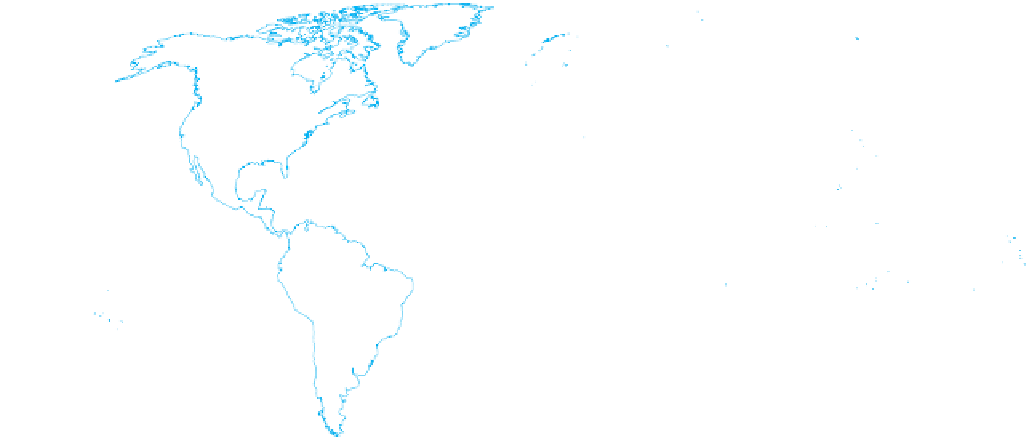

Figure 4.23

World Distribution of Skyscrapers.

Number of skyscrapers that are taller than 700

feet.

Data from

: Emporis, Inc., 2005.

forms and planning ideas have diffused around the world

(Fig. 4.23). In the second half of the 1800s, with advance-

ments in steel production and improved costs and effi -

ciencies of steel use, architects and engineers created the

fi rst skyscrapers. The Home Insurance Building of

Chicago is typically pointed to as the fi rst skyscraper. The

fundamental difference between a skyscraper and another

building is that the outside walls of the skyscraper do not

bear the major load or weight of the building; rather, the

internal steel structure or skeleton of the building bears

most of the load.

From Singapore to Johannesburg and from Caracas

to Toronto, the commercial centers of major cities are

dominated by tall buildings, many of which have been

designed by the same architects and engineering fi rms.

With the diffusion of the skyscraper around the world, the

cultural landscape of cities has been profoundly impacted.

Skyscrapers require substantial land clearing in the vicin-

ity of individual buildings, the construction of wide,

straight streets to promote access, and the reworking of

transportation systems around a highly centralized model.

Skyscrapers are only one example of the globalization of a

particular landscape form. The proliferation of skyscrap-

ers in Taiwan, Malaysia, and China in the 1990s marked

the integration of these economies into the major players

in the world economy (Fig. 4.24). Today, the growth of

skyscrapers in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, signals the

world city status of the place.

Reading signs is an easy way to see the second dimen-

sion of cultural landscape convergence: the far-fl ung stamp

of global businesses on the landscape. Walking down the

streets of Rome, you will see signs for Blockbuster and

Pizza Hut. The main tourist shopping street in Prague

hosts Dunkin' Donuts and McDonald's. A tourist in

Munich, Germany, will wind through streets looking for

the city's famed beer garden since 1589, the Hofbräuhaus,

and will happen upon the Hard Rock Café, right next door

(Fig. 4.25). If the tourist had recently traveled to Las Vegas,

he may have déjà vu. The Hofbräuhaus Las Vegas, built in

2003, stands across the street from the Hard Rock Hotel

and Casino. The storefronts in Seoul, South Korea, are

fi lled with Starbucks, Dunkin Donuts, and Outback

Steakhouses. China is home to more than 3200 KFC res-

taurants, and its parent company Yum! controls 40 percent

of the fast-food market in China.

Marked landscape similarities such as these can be

found everywhere from international airports to shop-

ping centers. The global corporations that develop

spaces of commerce have wide-reaching impacts on the

cultural landscape. Architectural fi rms often specialize in

building one kind of space—performing arts centers,

medical laboratories, or international airports. Property

management companies have worldwide holdings and

encourage the Gap, the Cheesecake Factory, Barnes and

Noble, and other companies to lease space in all of their

holdings. Facilities, such as airports and college food