Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

Field Note

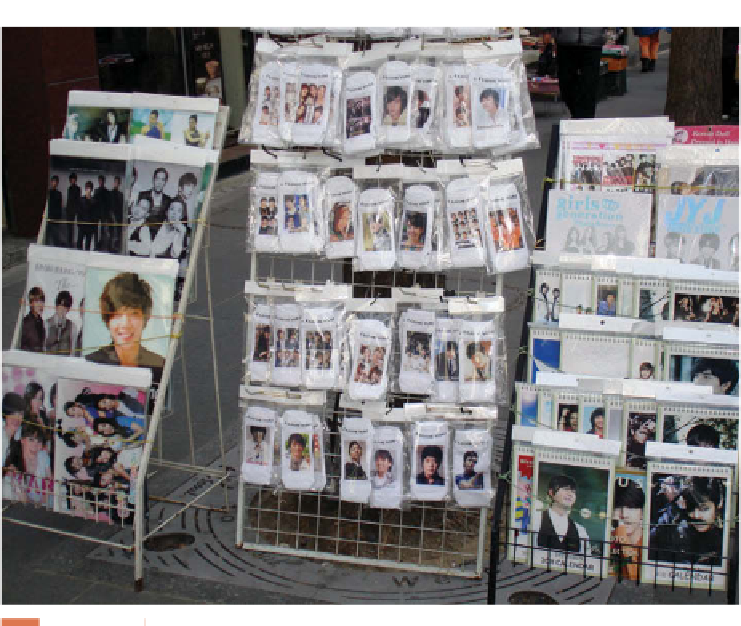

“Just days before the Japanese tsunami in

2011, I walked out of the enormous Lotte

department store in Seoul, South Korea and

asked a local where to fi nd a marketplace

with handcrafted goods. She pointed me in

the direction of the Insa-dong traditional

market street. When I noticed a Starbucks'

sign written in Korean instead of English,

I knew I must be getting close to the tradi-

tional market. A block later, I arrived on Insa-

dong. I found quaint tea shops and boutiques

with hand crafted goods, but the market still

sold plenty of bulk made goods, including

souvenirs like Korean drums, chopsticks, and

items sporting Hallyu stars. Posters, mugs,

and even socks adorned with the faces of

members of Super Junior smiled at the shop-

pers along Insa-dong.”

Figure 4.21

Seoul, South Korea.

©Erin H. Fouberg.

language classes, traveling and studying abroad in South

Korea, and adopting South Korean fashions.

A 2009 article in

Tourism Geographies

describes the

diffusion and proliferation of Hallyu in Asia:

benefi ted the French Hip Hop industry. By performing in

French, the new artists received quite a bit of air time on

French radio. Through policies and funding, the French

government has helped maintain its cultural industries,

but in countless other cases, governments and cultural

institutions lack the means or the will to promote local

cultural productions.

Concern over the loss of local distinctiveness and

identity is not limited to particular cultural or socio-

economic settings. We fi nd such concern among the

dominant societies of wealthier countries, where it is

refl ected in everything from the rise of religious funda-

mentalism to the establishment of semiautonomous

communes in remote locations. We fi nd this concern

among minorities (and their supporters) in wealthier

countries, where it can be seen in efforts to promote

local languages, religions, and customs by constructing

barriers to the infl ux of cultural infl uences from the

dominant society. We fi nd it among political elites in

poorer countries seeking to promote a nationalist ide-

ology that is explicitly opposed to cultural globaliza-

tion. And we fi nd it among social and ethnic minorities

in poorer countries that seek greater autonomy from

regimes promoting acculturation or assimilation to a

single national cultural norm.

Geographers realize that local cultures will inter-

pret, choose, and reshape the infl ux of popular culture.

Having fi rst penetrated the Chinese mainland, the

Korean cultural phenomenon of Hallyu, in particu-

lar Korean television, has spread throughout the East

and South-east of Asia, including Japan, Hong Kong,

Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam,

Philippines and later even to the Middle East and East

Europe. The infatuation with Korean popular culture

and celebrities has not stopped at popular media consump-

tion but has also led to more general interest in popular

music, computer games, Korean language, food, fashion,

make-up and appearance, and even plastic surgery.

When popular culture displaces or replaces local culture,

it will usually be met with resistance. In response to an

infl ux of American and British fi lms, the French govern-

ment heavily subsidizes its domestic fi lm industry. French

television stations, for example, must turn over 3 percent

of their revenues to the French cinema. The French gov-

ernment also stemmed the tide of American and British

music on the radio by setting a policy in the 1990s requir-

ing 40 percent of on-air time to be in French. Of the 40

percent, half must be new artists. These policies directly