Global Positioning System Reference

In-Depth Information

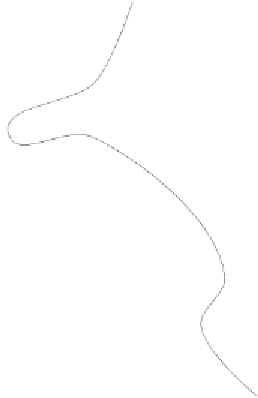

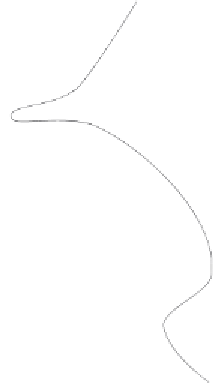

Our intrepid navigator might equally well employ a sextant to deter-

mine his position relative to the coast by referring to two coastal land-

marks, in which case he does not need to estimate his ship's speed because

this method works for a stationary vessel. In figure 7.2 we see that he is at

anchor and measures angles

a

and

b

from a common reference direction

(magnetic north, say) to two landmarks, the beacon and a large palm tree

atop a small hill. On his local chart he marks a

line of position

(LoP) for each

direction from each landmark. The intersection point of these two LoPs

indicates the ship's position.

In general, if a navigator has been estimating his position by dead reck-

oning (perhaps he has been in open ocean for some time, with no ter-

restrial reference points), then he might confirm his estimated position

upon sighting land by making a bearing measurement: the intersection

of one LoP with his dead reckoning track gives his position. Of course,

this method assumes that the landmark he spots was at a known loca-

tion, marked on the navigator's charts. For training purposes, a naviga-

tor might ask his midshipmen to estimate the ship's position by dead

reckoning as it weaves its way through an atoll of Pacific islands and then

FIGURE 7.2.

Getting a fix. A navigator or coastal pilot obtains a fix on his position

relative to a charted coast by measuring two lines of position—the compass direction

to two known landmarks or reference points on his chart. The intersection of the two

LoPs shows the navigator his position on the chart.