Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

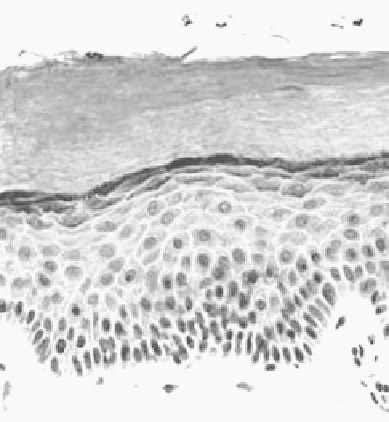

The protection provided by the epidermis forms the first barrier against harmful foreign

substances. Most of the cells (

90%) in the epidermis are “keratinocytes.” They produce a

tough, fibrous, and intracellular protein called keratin; hence the name. The keratinocytes

are stacked in layers. The youngest cells occupy the lower layers while older cells are pres-

ent in the upper ones. The lower layer cells multiply continually, while the older upper

layer keratinocytes constantly slough off. By the time the cells move up to the uppermost

layer of the epidermis, they are dead and completely filled with the keratin. From bottom

to top, the layers are named stratum basale, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, and

SC. Figure 10.4 shows the cross-section of the epidermis.

Various skin properties are routinely measured at the broadest classification level

whereby considering the entire epidermis as a single functional entity. Such information,

though essential, is incomprehensive, in that it does not account for the heterogeneity of

the epidermis. It is imperative to possess precise knowledge of the distinct properties of

each cutaneous component to design interfaces that interact individually with the cuticle

layers. SC in particular dominates various design considerations and is often times the

principal cause for development of micromachined interfaces.

10.3.2

Stratum Corneum

The outermost layer of the epidermis, SC, is a thin, flexible, high-impedance biopolymer

composed of interconnected “dead” cells called corneocytes. This complexly organized,

anucleate, 15-20-

m-thick, biopolymeric structure is essential to life and serves to couple

the organism to the environment. This structure is particularly well developed in humans

who lack a protective mantle of fur. It is the major barrier to all environmental insults (cli-

matic, toxic from xenobiotics, or microbial) [10]. Despite its resilience, it can bind a certain

amount of water to stay soft, smooth, and pliable even in a dry environment, thus allow-

ing free-body movement without cracking or scaling of the skin surface.

The underlying hypothesis in the development of bioengineered systems is that SC can

be a portal to the biological and physiological processes. It plays a major role in modulat-

ing sensory signals for visual and tactile perception. Also, the hydration status of SC is a

key determinant of the mechanical, electrical, optical, and chemical properties of the skin.

The properties of this layer serve as a health status indicator and valuable insights into the

SC

SGR

SS

FIGURE 10.4

Cross-section of epidermis [9]. (From Swanson, J. R.,

http://www.meddean.luc.edu/lumen/MedEd/medi-

cine/dermatology/melton/skinlsn/epider.htm.

Accessed May 15, 2005. With permission.)

SG