Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

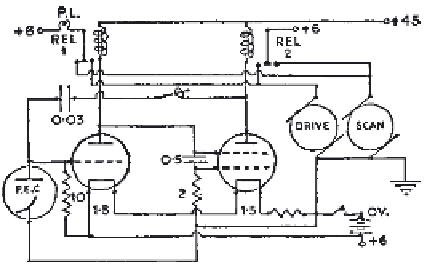

Figure 3.7.

The brain of the tortoise. Source: walter 1953, 289, fig. 22.

around when it picked up a light.

12

This interpretation found some empirical

support. As Walter noted (1953, 109), “There was the curious coincidence

between the frequency of the alpha rhythms and the period of visual persis-

tence. This can be shown by trying how many words can be read in ten sec-

onds. It will be found that the number is about one hundred—that is, ten

per second, the average frequency of the alpha rhythms” (Walter 1953, 109).

He also mentioned the visual illusion of movement when one of a pair of

lights is turned off shortly after the other. Such data were at least consistent

with the idea of a brain that lives not quite in the instantaneous present, but

instead scans its environment ten times a second to keep track of what is

going on.

13

From a scientific perspective, then, the tortoise was a model of the brain

which illuminated the go of adaptation to an unknown environment—how it

might be done—while triangulating between knowledge of the brain emanat-

ing from EEG research and ideas about scanning.

tortoise ontology

We can leave the technicalities of the tortoise for a while and think about

ontology. I do not want to read too much into the tortoise—later machines

and systems, especially Ashby's homeostat and its descendants, are more

ontologically interesting—but several points are worth making. First, the

assertion that the tortoise, manifestly a machine, had a “brain,” and that the

functioning of its machine brain somehow shed light on the functioning of

the human brain, challenged the modern distinction between the human and

the nonhuman, between people and animals, machines and things. This is