Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

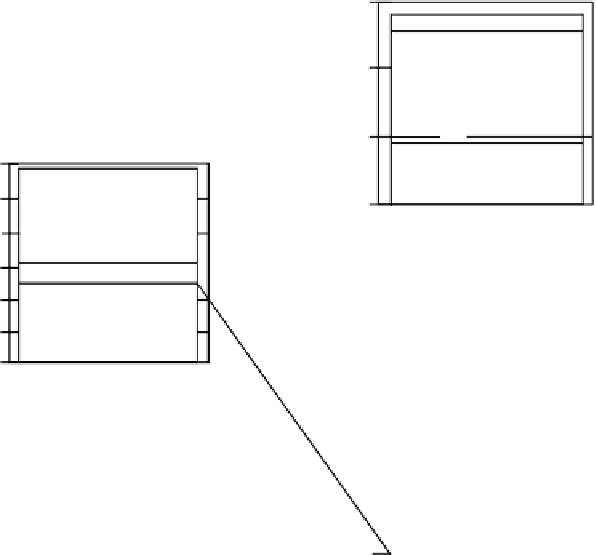

Nonmethane volatile

organic compounds (C

1

-C

10

)

15

Alkanes (1.47)

Olefins (2.45)

Aromatics and

naphthenes (0.2)

10

Carbonyls (5.48)

Organic compounds in

meat charbroiling emissions

5

Unidentified organic

compounds (4.58)

30

25

0

Non-methane volatile

organic compounds (14.2)

20

25

10

Non-volatile particulate

organic compounds (12.5)

Semivolatile and particle-phase

elutable organic mass

5

3.0

0

Aliphatic aldehydes (0.28)

2.5

Ketones (0.22)

C

l

otinic aldehydes

(0.15)

2.0

Alkanoic acids (0.48)

1.5

Alkenoic acids (0.32)

O

ther (0.00)

1.0

Particle-phase unresolved

complex mixture

(UCM).(1.30)

0.5

0.0

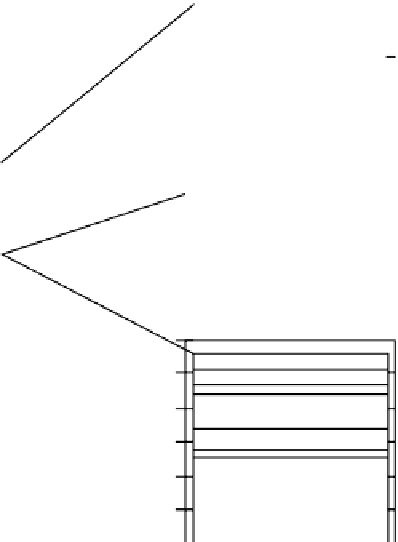

FIGURE 6.3

Chemical composition of emissions from charbroiling meat. (From Schauer, J.J. et al.,

Environ.

Sci. Technol

., 33, 1566, 1999a. With permission.)

cooking would lead to at least twice the dose of PM

2.5

(by mass) as a person would receive during

1 h spent outside in downtown Toronto, Ontario, Canada. A second phase of the study involved

monitoring emissions from heating the same amount of cooking oil in ive different homes, all of

which had exhaust fans to control exposure to PM from cooking before the particles could mix

with background air and PM. They found that the average estimated dose was at least an order of

magnitude higher than in the irst part of their study. The authors attributed the difference to their

observation that low rates for the exhaust fans were up to an order of magnitude lower than the

manufacturers' speciications.

6.2.1.1.2 Cooking with Solid Biomass Fuels

As of the end of the irst decade of the twenty-irst century, solid biomass fuels (SBF) such as wood,

charcoal, agricultural waste, and animal dung are the fuel sources for at least a third of the world's

population. Widespread exposure to high levels of PM from cooking with SBF has been shown to

increase risks of respiratory problems (Padhi and Padhy, 2008; Po et al., 2011), cardiovascular dis-

ease (e.g., Dutta et al., 2011), and cancers (e.g., Wu et al., 2004) in Asia and Africa—the developing

world (Fullerton et al., 2008).

Besides causing severe health problems and shortening life spans from chronic exposure to

smoke from SBF, cooking with SBF in ineficient stoves contributes signiicantly to global CO

2

and

particulate pollution. The U.S. EPA (2010) estimated that replacing one ineficient stove reduces

CO

2

-equivalent emission by about the same amount as taking one car off the road in the United

States. A recent review of worldwide biomass emissions by Akagi et al. (2011) indicates that emis-

sions from open cooking and cooking stoves contribute one teragram per year of black carbon (soot)

to the global atmosphere. Table 6.5 shows their compilation of emission factors for major pollutants

from combustion of the types of SBF used indoors.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search