Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

Cremation at the Tschudi Burn

C

olonel La Rosa

s commentary and, now, elevated calcium and phosphorus were very suggestive that cremation

may have occurred at the Tschudi burn

'

yet, the anomalous calcium and phosphorus content of the soil could be

explained as coming from other sources. Therefore, if the Tschudi burn had actually been used for cremation, only

the presence of calcined human bone would be definitive.

—

Calcined bone generally survives longer in the soil than unburnt bone. This is due to a case-hardening effect and

increased density brought on by heating, recrystallization, and conversion of the bone material (hydroxapatite) to

β

-tricalcium phosphate. Then, upon cooling, water is absorbed and the bone reverts to a more coarsely crystalline

hydroxapatite which may contribute to its survival in the soil. Heating also destroys the organic component of bone

which would attract organisms that would ultimately destroy the bone (Mays, 1998, p. 209).

Since cremation is a destructive process, it is important to consider which bones and how much material might

remain. At the Museo Arqueológico Naciónal in Madrid, a diorama showed that at the prehistoric Necropolis de

Medellin, after cremation took place, bone was recovered and placed in a stone receptacle. In another example,

Bronze Age cremation studies in Europe showed that no more than 60% of the bone weight may be recovered

(McKinley, 1998). Some of the more commonly occurring bone fragments that remain after cremation include

parts of the vertebra, the mandible, or temporal bone and most fragments are small, in the 2

-

4 mm range (Mays,

1998, pp. 210

-

213). After a modern cremation, which takes place at temperatures of 800

-

1200°C for only

-

2

3 hours, the larger, more-dense, weight-bearing bones, such as femur, hip, jaw, and perhaps a part of the

skull, will remain somewhat intact. Depending on bone structure, only 5

-

7 lb of bone will remain after cremation

and this material must be uniformly crushed before the cremains or

are returned to the family (Bloomquist,

1996). Any of these bones, if still present at the Tschudi burn, would have been conspicuous, found, and described

by previous researchers. However, given the duration of the Tschudi burn, some bones may have been completely

consumed in the 16

“

ashes

”

40 hour, 1320°C fire. Or, bone may have been removed after cremation for secondary

burial, scattered by scavengers or looters, or simply degraded after more than 600 years of exposure.

-

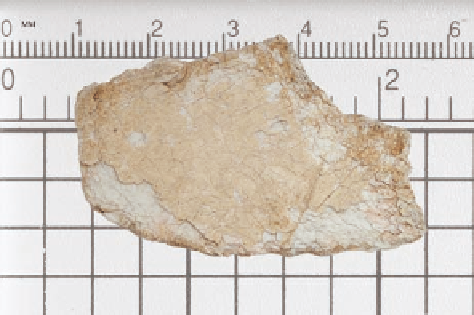

In May 2005, a 5 gm, 4.5 cm bone fragment was found. The fragment had weathered out of excavated material

from the research trench that was dug in the 1970s. The bone fragment was angular and considered in-place as any

rounded edges would have indicated that it washed in among the sediments that underlie the burned material. The

fragment was described as consistent with calcined bone from the cranial vault, likely the subparietal bone, of a

youth and showed meningeal vessel grooves on the interior surface (Figure 4.1.3). Protein radioimmuno assay

(pRIA) was recommended to confirm its human or other origin (Douglas H. Ubelaker, Ph.D., anthropologist,

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, oral communication, June 20, 2005). The fracture pattern on the surface

is irregular and shows splitting, all consistent with the fracture pattern of bone that was fleshed when burned

(Ubelaker, 1978, p. 38). The fragment was denser than unburned bone because of heating and recrystallization

(Mays, 1998, p. 207).

A

B

Figure 4.1.3. Calcined cranial vault fragment (B0502) from the Tschudi burn. (A) exterior, showing fracture

pattern typical of bone that was fleshed when burned and (B) interior, showing meningeal vessel grooves. Photo by

William E. Brooks, 2005

.