Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

of Tertiary times in Europe, these youngest rocks provoked puzzle rather than

resolution. The middle or so-called Secondary strata (including what we now call

Mesozoic and the top part of the older Paleozoic) yielded first to the new methods.

These rocks are ordered throughout Western Europe in the nearly ideal configurations

of textbook dreams—as extensive sheets of minimally distorted, flat-lying or gently

tilting beds, easily traced over large areas. For example, the distinctive

"chalk" (forming, for example, the White Cliffs of Dover), top layer of the Secondary,

blankets this region with little complexity in deposition or later distortion—you really

can't miss it, as the saying goes.

By contrast, the younger Tertiary strata are deposited as a complex patchwork in

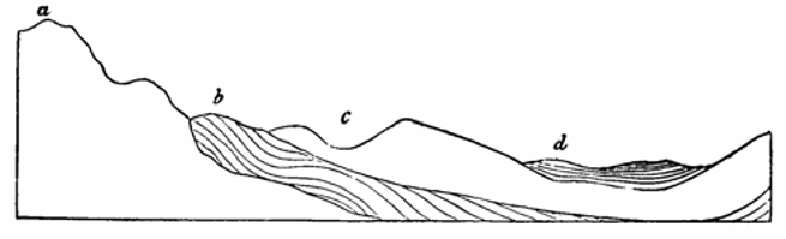

isolated basins—the bane of any stratigrapher's existence (Figure 4.7). Geologists work

by correlation and superposition—fancy words for the obvious techniques of

ascertaining what beds lie atop others (superposition), and then tracing this order from

place to place (correlation). But if strata are clumps

a

, Primary rocks.

b

, Older secondary formations,

c

, Chalk.

d

, Tertiary formation.

Figure 4.7

An illustration of the problems faced by geologists in unraveling Tertiary stratigraphy.

Tertiary rocks of Europe tend to occur in small and isolated basins (as in d above),

making correlation difficult. (From first edition of Lyell's

Principles

.)

Search WWH ::

Custom Search