Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

500

500

Moist crop - day

Moist crop - night

400

400

Latent heat

dominant

300

300

200

200

100

100

R

n

A

l

E HGS

t

0

0

R

n

A

l

E HGS

t

Forest reflects

less solar so

R

n

is greater

−

100

−

100

500

500

Moist forest - day

Moist forest - night

400

400

Latent heat

Less dominant

Little

soil heat

storage

300

300

200

200

100

100

R

n

A

l

E HGS

t

0

0

R

n

A

E HGS

t

l

−

100

−

100

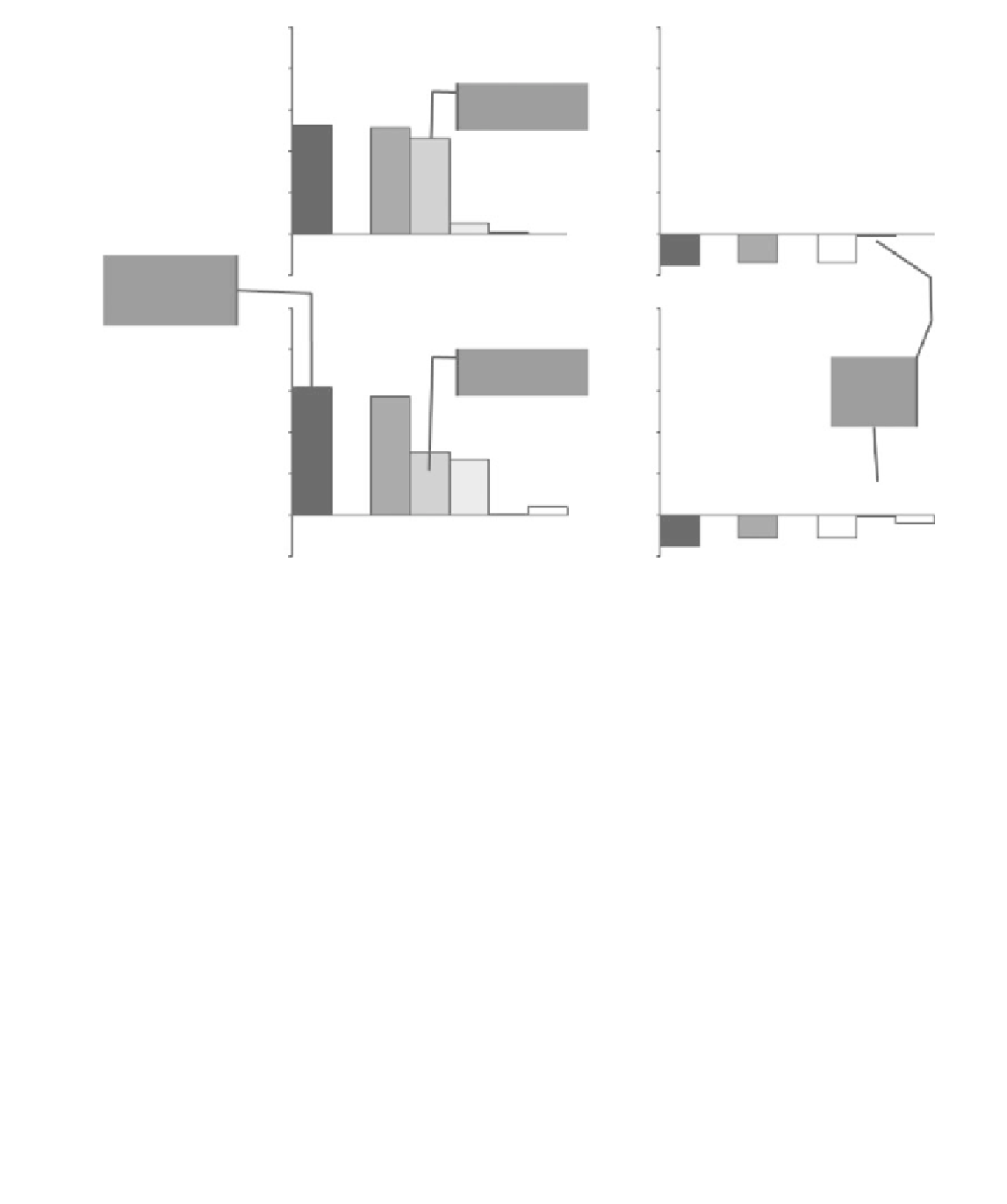

Figure 4.4

Representative daytime and nighttime surface energy budget for short crop and forest when there is plenty of

water available in the soil.

heat flux dominates outgoing sensible heat during the day for wet soil. The outgo-

ing net radiation flux at night, which is entirely longwave radiation, is supported

partly by energy returning to the surface as soil heat flux and partly by an inward

flux of sensible heat flux, the latter being the more important contribution in the

dry soil example.

Figure 4.4 shows representative daytime and nighttime surface energy budgets for

a short crop and for forest. In each case there is plenty of water available to the veg-

etation in the soil. Again, downward solar radiation,

S

, is assumed to be 350 W m

−2

for the daytime examples, nighttime net radiation flux is assumed to be

75 W m

−2

,

and nighttime evaporation is set to zero. For short annual crops (including

grass), both of the storage terms,

S

t

and

P

are negligible, but in the case of forest

physical energy storage can be significant. In Fig. 4.4, both the short and forest

vegetation are assumed to fully cover the ground and as a result the soil heat flux

is small in both cases. But

G

is particularly low for forest vegetation because the

leaf cover is greater. Forests usually reflect less solar radiation than short annual

crops because the top of the canopy is rougher, consequently the net radiation

input tends to be higher during the day. For well-watered crops, most of the avail-

able energy is used for evaporation during the day and the outgoing latent heat

−