Travel Reference

In-Depth Information

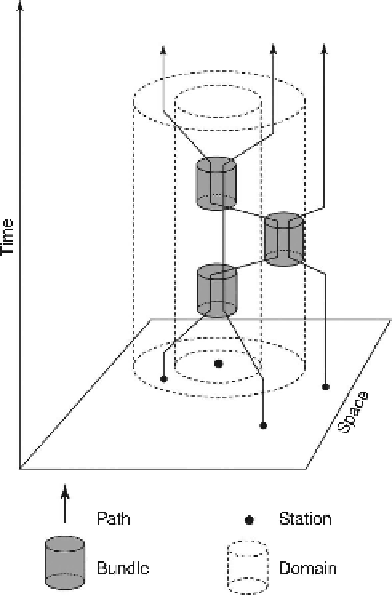

Visualisation of space-time paths

One of Hägerstrand's most profound professional and disciplinary achievements was the

ability to represent space and time in a single diagram (Gren, 2001), unlike an ordinary map,

but rather like a snapshot, that reproduces a moment frozen in time. The result was his, now

famous, time-geographic diagrams: notational (representational) systems, which formed the

basis of much of the subsequent work in the fi eld of time geography, particularly in the realm

of analysis and interpretation. The diagrams (see

Figure 22.1,

taken from Gregory, 1989)

consist, as a rule, of two axes: a time-axis and a space-axis, thus making it possible to trace in

graphic terms individual time budgets. The effective range of each person is described by a

prism, or a series of prisms, whose shape is dependent upon the aforementioned capability

constraints. Hence, every pause, regardless of the activity involved, will cause the prism's (or

sub-prism's) range to shrink in direct proportion to the time spent at said stop. But there are

also other wider structural features, specifi c to the social systems within which individuals

operate, which, as has long been recognised, help shape people's time budgets and activity

patterns.

As long as most of the work in time geography was primarily theoretical, there was little

problem in presenting of time-space activity in such a manner. Indeed, the majority of studies

published in the 1970s and 1980s presented one, two or, at the most, four sequences (see, for

example, Parkes and Thrift, 1980). The method was until recently less suited for empirical

research purposes, where there is often a need to incorporate a large number of sequences on

the dual axis. In such cases, several problems arise: some visual, others analytical. To begin

Figure 22.1

Hägerstrand's time-geographical diagram