Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

nomads. Each year, they migrate to high altitudes during spring and early summer, after

the snow melts and relatively lush grasses develop in the mountains. Meanwhile, dry

heat withers the lowlands. When winter approaches in the high country, autumn rains

and clouds green the lowland grasses, spurring a return to the plains. This seasonal cas-

cade of favorable conditions between high- and low-altitude pastures underlies the eco-

logical basis for nomadic pastoralism. It should be stressed, however, that nomadism is

a cultural decision, not one forced by environmental conditions. Other approaches may

be equally successful, as demonstrated by the many sedentary agriculturists who share

terrain with nomads. Examining history makes this fact even more astonishing. For ex-

ample, before the twelfth century, Iran, Anatolia, and much of Afghanistan supported

sedentary agriculturalists. It was only after the Turk-Mongol invasions of the Middle

Ages ravaged farmland that nomadism became important here.

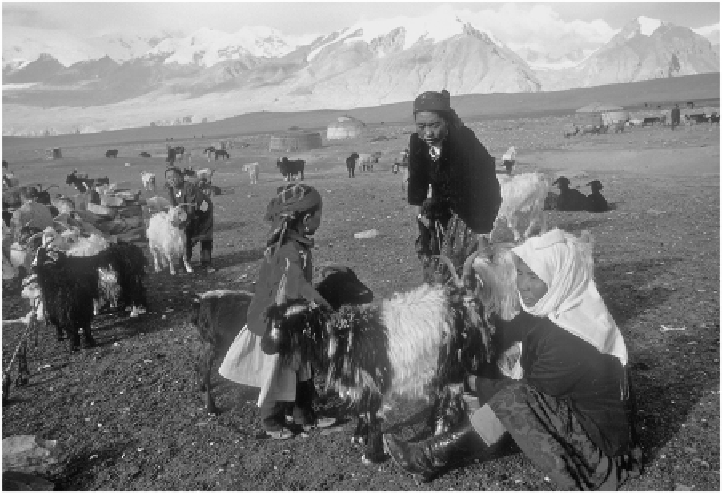

FIGURE 11.14

Kirghiz pastoralists milk goats in the Chinese Pamir. (Photo by S. F. Cunha.)

Today, nomadic pastoralism in mountain regions is found primarily on three con-

tinents. These include the Old World highlands of East Africa, the Atlas Mountains of

North Africa, the Mediterranean Balkans, Scandinavia and Siberia, Zagros of Iran, the

Afghan Hindu Kush, the western Himalaya, and Central Asia's Pamir, Tien Shan, and Al-

tai Mountains. The common livestock includes sheep, goats, and cattle, although camels

(North Africa), reindeer (Scandinavia and Siberia), horses (Mongolia), and yaks (Central

Asia) are locally important. New World nomadic pastoralism is restricted to the Andes,

where llamas and alpacas are raised. Pastoralism is not generally found in eastern Ch-

ina or Japan, owing to the traditional emphasis on intensive cultivation, or in North

Search WWH ::

Custom Search