Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

riculture strategies are

traditional

is problematic, as they are often thought to descend

directly from ancient and somewhat unchanged practices. In reality, farming and animal

husbandry evolve significantly over time in even the most isolated mountain societies.

What we see today may bear little resemblance to what existed in previous times. The

evolving cultural landscape reflects a human response to specific environmental condi-

tions. Despite a lack of machinery and techniques common in many lowlands, “the

tra-

ditional

farm systems are as

modern

as any other in that they are products of contem-

porary processes” (Brush 1988: 116). The decline of alpine agriculture in the Alps and

North America because of mechanized competition from lowland farmers, combined

with their proximity to urban markets, further explains our emphasis on developing re-

gions.

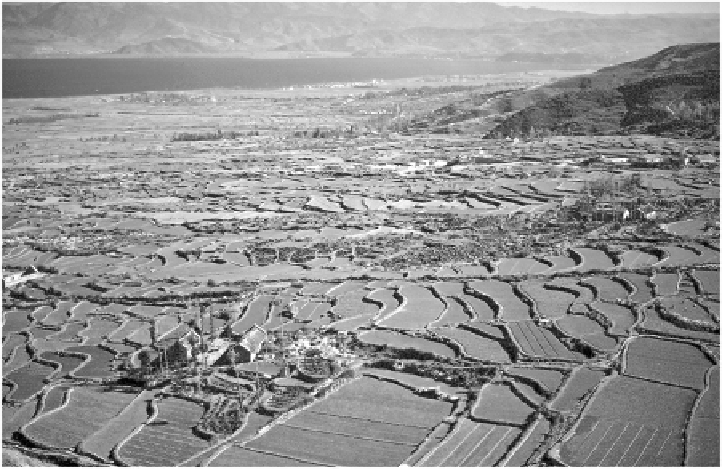

FIGURE 11.1

Terraced fields above Dali, Cangshan Mountains, southern China. (Photo by S. F.

Cunha.)

Going Vertical

The vertical distribution of different environments and, in extratropical areas, the dif-

ferent seasonal conditions at each level, demands a staggered schedule for exploitation.

Each elevation is most ideal for growing specific crops or for certain animals to graze.

This

verticality

concept occupies an important position in mountain studies, and was

illustrated by Alexander von Humboldt's classic nineteenth-century

schemata

of alti-

tudinal zonation, or upward progression of changing vegetation and landforms in the

Andes (Helferich 2005). His early model (Fig. 11.2) identified Latin American subsist-

ence adaptations to distinct life zones. Sugar cane, maize, poultry, and pigs flourished

in the lowland

tierra caliente

below 900 m (3,000 ft). The higher and cooler

tierra tem-

Search WWH ::

Custom Search