Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

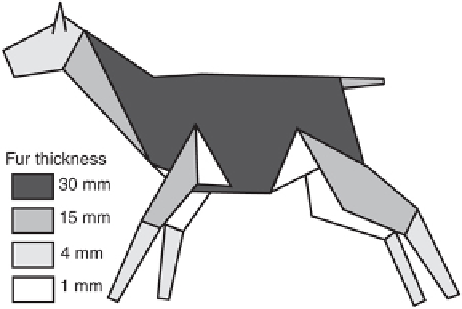

FIGURE 8.13

Diagrammatic representation of fur thickness on the guanaco (

Lama guanicoe

). The

large variations in insulative quality from its back to its underbelly allow the animal to adjust to a

wide range of temperatures (After Morrison 1966: 20.)

The amount of insulation on an animal is variable in space and time, owing to the

need to both dissipate and conserve heat. Thus, certain areas of the body, especially

the head, legs, and underbelly, may have thinner insulation than the rest. The guanaco

(

Lama guanicoe

) of the high Andes has densely matted fur on parts of its body, while

other areas are almost bare (Fig. 8.13). This animal lives in a dry environment, with in-

tense sun and heat during the day but rapid cooling and freezing at night. The variable

insulation of the guanaco is designed to allow maximum flexibility (Morrison 1966).

When the animal is hot, it can expose the more thinly insulated areas, but when cold,

it can curl up and protect itself. This behavior is common in all animals. The mountain

sheep rests with its legs extended during warm weather but, when it is cold, it tucks

them under its body. Similarly, the fox or the wolf coils into a tight ball and wraps his

long bushy tail across his face. Birds tuck their heads under their wings. The ability of

fur or feather to insulate may also be controlled to a certain extent by flexing the fur or

fluffing feathers to create more dead air spaces. Alternatively, the hair may be wetted or

sleeked against the body, allowing greater heat loss. This is frequently associated with

evaporative cooling through sweating and panting.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search