Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

eries in the last three decades of the 20th century, however, piled one type of evidence

upon another so heavily that the conclusion became inescapable—the continents had

indeed moved apart (Strahler 1998).

One of the first modern discoveries was made in the early 1950s by geophysicists

studying rock paleomagnetism. When molten volcanic rocks with traces of iron solidify,

the rocks are slightly magnetized in the direction of Earth's magnetic field. It follows

that molten rocks formed at about the same time on different continents should be like

compasses with their needles frozen in the direction of the Earth's magnetic pole, but

it was discovered the orientation of similar ancient rocks on different continents did not

line up with the Earth's present magnetic field. This suggested that either the poles had

“wandered,” or the continents had moved with respect to the magnetic pole. Because it

is generally believed that the Earth's magnetic and rotational poles have always been

close to each other (within 15°), the continents were assumed to have moved, but the

mechanism for this movement was still unknown.

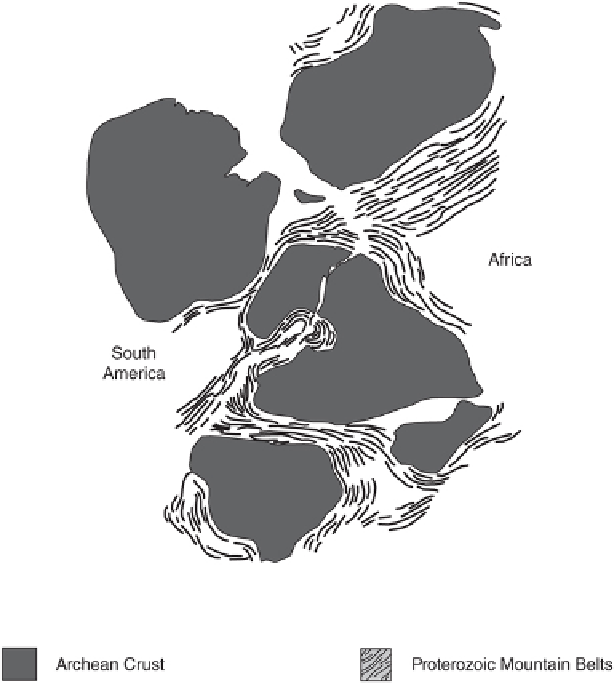

FIGURE 2.5

The “fit of the South American and African continents around the south Atlantic Ocean,”

showing close conformity of coastlines, continental shelves, Achean crustal blocks, and trends to

Proterozoic mountain belts. (Adapted from various sources.)

Search WWH ::

Custom Search